An eerie chill went through me when I saw the news report. The remains of 215 children had been discovered in a mass grave in Canada. Just hours before I had been editing an article about an exhibition, Artivism: The Atrocity Prevention Pavilion, showing how art is used as a response to identity-based mass atrocity — including those at residential schools in Canada.

Those children, some as young as three, had been students (captives seems a more appropriate term) of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. Their deaths are believed to have been undocumented.

The news came as a shock to some in other parts of the world, but it wasn’t a surprise to the indigenous people of Canada.

As Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir said in the press release announcing the “stark truth” of the discovery: “We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify.”

Indigenous people in Canada, like so many others whose land was brutally colonised, have suffered numerous atrocities — with residential schools playing an integral part. The suffering continues, however, long after those awful gates were shut, long after some of the grisly buildings were demolished and even after a Truth and Reconciliation Commission sought to bring closure and compensation.

These schools (which also seems an incongruous term) were part of a governmental system, administered by Christian churches, with the aim of taking “the Indian out of the child”. They severed children from their families and cultural practices to assimilate them into the Eurocentric “Canadian” way of life.

Children were forcibly taken from their homes and housed in boarding establishments where they suffered physical, emotional and sexual abuse. They were not fed or clothed adequately and were forbidden from speaking their own languages or carrying out any family traditions. More than 6000 are known to have died.

The system has been called “Canada’s dark secret”.

But it is certainly a horror recognisable to South Africans — and we find similar examples in any settler colonial society, Kerry Whigham of the Auschwitz Institute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities told the Mail & Guardian from New York.

“People have been made victims because of their identities, through the establishment of a system that is still in place today,” he says.

In Australia from 1910 to the 1970s, Stolen Generations of Aboriginal children were taken from their parents to be “re-educated”, today asylum seekers are held in prison-type camps there. There was the Herero and Namaqua genocide in Namibia (1904-1908); now there is the persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar and the Uighurs in China. Conversion therapy seeks to force someone’s sexual identity and developers still want to bulldoze land for Amazon offices knowing full well it is sacred to the Khoikhoi and San people in Cape Town.

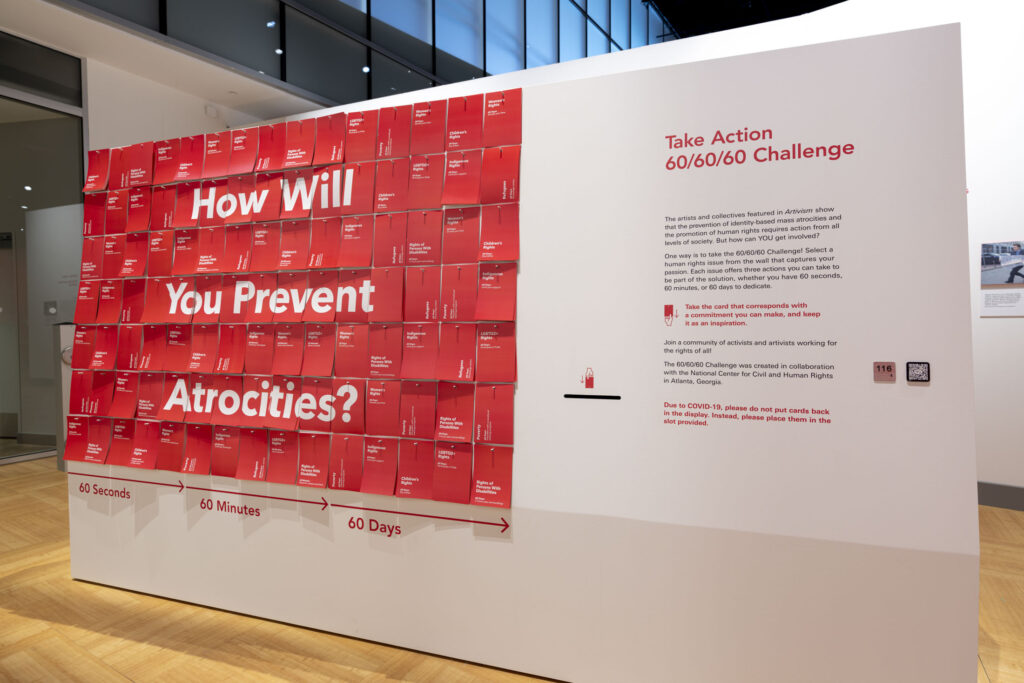

“The discovery of the mass grave in Canada is further proof that atrocities happen not only in the past or elsewhere, they happen everywhere and they still happen,” says Whigham, who is a curator of Artivism.

It is one of the points that the exhibition sought to highlight by choosing a group of six artists from geographically diverse regions (including the Intuthuko Embroidery Project from South Africa) to show how art is used all over the world to heal trauma and resist such iniquities both past and present.

Bearing witness through art

Artivism first showed at the 2019 Venice Art Biennale and then moved to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, where it opened at the end of April — about a month before the Kamloops burial site was confirmed.

Housed alongside it at this museum is The Witness Blanket, an art installation by master carver Carey Newman (Hayalthkin’geme) which is a commemoration of all those who passed through the residential school system, and those who never made it out.

The work resembles a woven blanket crafted from cedar blocks threaded on wires and adorned with about 800 items collected from residential school sites, survivors and families.The churches and federal government also donated pieces as a gesture towards reconciliation.

“I made it for my father who is a residential survivor,” Newman told the M&G. “I am also a survivor, through my father.”

Newman and his team travelled around the country visiting sites, speaking to survivors and their families and gathering the objects, such as shoes, photographs, books or letters, that were used to tell the inside story.

“I learnt about my dad through the words of others,” he says, adding that his father, Victor, could never bring himself to speak about the worst of the abuses he endured at St Mary’s Mission Indian Residential School.

The experience was transformative for the family — his parents, two sisters, wife and himself. He said he suddenly understood things that he could never quite get a grip of while he was growing up. There were deep-seated reasons for his father’s “gruffness” after all.

“I thought of myself at seven … that’s how old he was when he was taken there.”

to help tell the story. They bear silent witness. Photos: Jessica Sigurdson/CMHR

The myth of Canada

Newman has said that his role as an artist is to bear witness, but that we all are — or should be — witnesses and speak about what we have seen and heard.

He is, however, underwhelmed by the Canadian government’s attempts at speaking up and taking action.

“[Prime Minister Justin] Trudeau referred to it as a dark chapter in our history,” he says of the prime minister’s earlier remarks about the unmarked graves.

Newman says that the consequences of that time are very much a part of the present and reveal themselves in the inequalities that indigenous people still face, such as lack of clean water or inadequate health care as well as the intergenerational trauma such as children being in government care because their parents haven’t healed; and the persistent view that they are an inferior race in need of paternalistic supervision.

“Canada is always protecting its image as a multicultural society where everyone is welcome. This [discovery] puts a crack in that veneer. For a country to mature, it needs to be real and reconciled to the truth.

“But while they say they subscribe to the UN’s rights for indigenous people, there is always a caveat. It is too scary for them to share the land.”

He says the Canadian government needs to openly acknowledge that the country’s foundations, wealth and reputation have been built at the expense of the language, culture, lives and wellbeing of its original inhabitants.

But, the Kamloops discovery has had a startling effect and is gathering momentum; Newman says in all his years of doing work advocating for indigenous rights, he has never had so many calls from around the world. “It is the first time I have heard it being referred to as genocide from the outside,” he said.

It was reported by The Canadian Press on Saturday that Trudeau had to concede: “To truly heal these wounds, we must first acknowledge the truth, not only about residential schools, but about so many injustices both past and present that Indigenous Peoples face.”

The report went on to say that such admissions could have legal consequences and that lawyers have requested the International Criminal Court in The Hague to investigate the Canadian government and the Vatican for the findings in Kamloops.

Quoting political science professor David MacDonald from Guelph University, the report said that unlike Germany, if Canada admits to genocide, it would not just be admitting that “some earlier and completely different government committed genocide … it would be admitting that the genocide occurred by the hands of institutions that still function more or less now as they did before”.

An echo of Newman’s words and convictions.

Perhaps it will also have a bearing on his fight to save the 37 000 or so survivor statements that were used to settle abuse claims as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

People could receive compensation if they went through the Independent Assessment Process (IAP) by telling their stories. These records are now part of a supreme court case because the authorities want to destroy them.

“They say it is on privacy grounds, but it is unconscionable to think we can get rid of these documents,” says Newman, who is part of a coalition working to save them for posterity.

Similar survivor stories are available in a documentary Newman has made and which is free to watch on the museum’s website titled Picking up the Pieces: The Making of The Witness Blanket.

In it a sister remembers her brother’s unexplained suicide, an elderly man explains why it is not simply a case of “getting over it”, another says he is sorry to say, but he hates the white man, another asks “why don’t you just go and take their children away and see how that feels?” There are proclamations of love for the land, traditions and rituals, pride in belonging to the First Nations groups. There are smiles and shrugs, shouts and tears.

The film is accompanied by a note: “Watching this documentary allows you to witness the making of this powerful artwork and the survivor stories it bears. Artist Carey Newman says: ‘In the Salish tradition, we ask people to stand and speak about what they have witnessed.’ We ask you to share its stories and your own story of encountering them, and to weave these memories and experiences into your life in living remembrance.”

As a South African you cannot but be moved by these artworks and film; so many of their stories echo ours. I had to share my encounter with it.

happens at the interpersonal, individual level. We all have something to contribute,’ says Kerry Whigham. Photos: Aaron Cohen/CMHR

Photographs by Jessica Sigurdson and Aaron Cohen supplied by the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR).