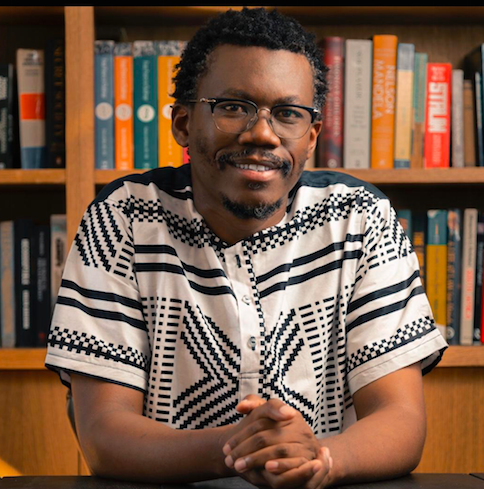

In the second of a three-part series on South Africa’s land question, Tembeka Ngcukaitobi says the constitution is clear: land seized under colonial states must be returned. But there is only policy confusion and elite possession

It is time to call out the ANC’s inertia on land. In the 1990s there was urgency to address the land inequalities. The Reconstruction and Development Programme contained expansive provisions on land, the Ready to Govern document was bold and imaginative, the White Paper was bristling with creativity and the Constitution contained a legally enforceable framework for the fundamental transformation of land relations.

The Constitution’s message was clear and unequivocal: the land relations of the colonial and apartheid past had to be changed in favour of the dispossessed African majority. The ANC’s praxis in government also supported this vision of the Constitution. The Commission for the Restitution of Land Rights was set up, a government department was provided with an infrastructure to administer land reform and the land claims court was established to provide judicial oversight over the land reform programme.

To begin with the Constitution’s meaning has never been incapable of judicial interpretation, either in its purpose or its letter. The few judicial determinations in the early years of the Constitution affirmed its decolonial ethos as far as land was concerned. Farmworkers’ rights to be buried in the land where they lived were recognised. Rights to restoration of land, above financial compensation, were emphasised. Landowners’ rights to receive market based compensation — despite state policy – were curtailed. Landowners knew that under the Constitution they could not expect exorbitant compensation from the state, but would be paid whatever was deemed just and equitable. Land ownership claims by labour tenants over the land where their predecessors worked against their will, were enforced. Although there was no law regulating redistribution, state policy sanctioned it. And state officials got on with the job of farm distribution — at a slow pace, but the point is that some people obtained access to farmland.

Things began to slow down, then stagnated, then fell apart. Precisely when this occurred is not easy to date, but figures presented by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies at the University of Western Cape point to signs of decline in the land reform programme some 15 years ago already. More people living in farms lost their rights of residence. Budgets for land reform were cut, land compensation moved from merely market based to stratospheric — the owners of the Mala-Mala were a perfect illustration of this new phenomenon in 2012.

For context, some facts are necessary as the Mala-Mala case tends to evoke more outrage than clarity. The land claims court had concluded that the state could not pay the owners less than R790-million. The state’s own valuers believed the appropriate amount to be R460-million. The case was due for argument on appeal at the constitutional court where one of the issues to be answered was the extent of just and equitable compensation to be paid. Inexplicably, a few days before the hearing, in February 2013, the staggering sum of R1.1-billion was offered by the state, for the same land it had previously valued at less than half the amount.

There was no transparency about the state’s decision-making process or justification for it. Notably in the few months before the settlement, the state had announced its intention to jettison the willing-seller, willing buyer approach. Yet the deal went ahead, in sums that were much more than the market would have been prepared to pay. This deal set the tone for the land crisis that was to unfold. The commission was gutted of key staff and personnel, no longer able to produce credible and reliable research reports on the histories of communities who were dispossessed of land. Land claims court judgments are replete with examples of judicial rebuke for dilatoriness and incompetence against the commission. Claims for restitution piled up. In 2013 the government attempted to reopen the restitution claims process without finalising existing claims. Some 80 000 new claims were lodged after 2013, despite the thousands of the unresolved claims, since 1998, which were pending at the commission. It seemed that the commission had lost its capacity to perform its statutory duty.

The department wasn’t doing better either. Under the law, it is the function of the department’s director general to administer the labour tenancy programme, whose primary aim is to facilitate the acquisition of land for the benefit of labour tenants. Claims for the ownership of land had to be submitted by March 2001. More than 11 000 claimants came forward. But they were met with “administrative lethargy”. Nothing happened. The applications were allowed to pile up at the offices of the department, compelling the claimants to seek legal redress. The incompetence in the programme was so severe that labour tenants were compelled to ask the courts to outsource the function, so that it is run by an independent person, called the “special master”. This is an indictment. It is extraordinary for a state department to be incapable to the extent that statutory powers must be relocated to a separate body.

Institutions for land reform have simply failed. But the problem doesn’t end there. It is deeper. Much, much deeper. I began this piece by reflecting on the early 1990s. In this period while state institutions were being established, there was imaginative intellectual work being undertaken to support the reform agenda. These days, there is a noticeable void in the policy arena. Since 2017, when the ANC decided on expropriation without compensation as one of the policy options to drive the land reform agenda, not much policy work has been undertaken either by the party or its government on the subject. No green paper. No white paper. Nothing. It seems that there is no clear end-goal. The process appears to be driven by a series of trials and errors.

Recently a new idea has emerged from the Economic Freedom Fighters: state custodianship over land. ANC representatives in parliament have appropriated some elements of the idea, as the concept now also appears in their own draft version of the constitutional amendment to section 25. Yet the ANC hasn’t — at least publicly — produced a guiding policy framework, addressing the most elementary aspects to the proposal, answering the what, when, how questions. This is important given the multi-dimensional nature of state custodianship. Notable are recent pronouncements by the Kwazulu-Natal high court about a different form of custodianship over land, that of traditional leaders. The court has now affirmed the rights of ownership and beneficial occupation of the people residing on the Ingonyama Trust land. Clearly, as this judgment illustrates, custodianship doesn’t mean ownership and existing rights, whether customary or otherwise, can be stripped away. Quite the contrary. This is why policy clarity is necessary.

We have no clue of what the ANC’s understanding of state custody is. The ANC doesn’t appear to know either. On 3 June, its parliamentary representatives proposed a new section 25(5), which reads: “The state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, tofoster conditions which enable state custodianship and for citizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis.”

Yet that same week, President Cyril Ramaphosa rejected state custodianship.

It is also not clear how state custodianship fits with general ANC policy on land, which has prioritised individual ownership above everything else. Actually, for 27 years the state has been wedded to the trajectory of an individualistic and unbridled free market capitalism, punting more, not less private ownership of land. This has included the privatisation of communal land. Evidence of “economic growth” from these market based solutions has been scarce. But these notions are advanced as the solution. Experiences from economically depressed areas such as Joe Slovo in Cape Town, where the state experimented with freehold, proved that banks will lend to the unemployed on production of title deeds is fictitious. This added a new dimension of suffering as surveyed land also meant new charges of municipal rates to an already impoverished people. This adds to the general problem that we seem to have no comprehensive land strategy behind some of the actions of the state.

State custodianship over all land has not always been part of the debate. When the public debate commenced, in 2018 the focus was on expropriation without compensation. Now it has morphed into state custodianship and expropriation without compensation, itself reflective of the general trend that significant policy decisions appear to be made on the fly. The critique of the process does not mean we should lock out of the debate state custodianship. It is possible that one of the future policy options should include it. But it must be clear which version of state custodianship is being considered: is the proposal to abolish private property, or to give the state expanded administrative powers over land, while ownership remains unchanged?

Public deliberation is not only necessary for reasons of legitimacy of the ultimate decision, it is also required to test the extent to which the forms of custodianship under consideration will affect existing security of tenure and facilitate access to land on an equitable basis. The Constitution guarantees security of tenure and equitable access to land. Any constitutional amendment cannot result in tenure which is less secure or limit access to the land by the people, who need it.

There is a version of state custodianship at the moment. The state buys farms from private landowners, often an exorbitant process, on unclear criteria. It then keeps these farms. Emerging farmers may apply to lease these farms. Some succeed but many do not. Research in the Eastern Cape by Ruth Hall and Thembela Kepe showed “elite capture” in the programme — people with no farming experience or interest got the farms at the expense of genuine small-scale farmers. All because of political connections. Some of the farms are leased out, but others are “sold” to qualifying beneficiaries. There is no proper financial accounting about the funds collected from the leases. Nor is clear how the state decides on the lease amount. When the farms are sold there is neither a public process, nor an auction — no rational justifications appear to exist for this secrecy in the lease and sale of state farms. For years this state incapacity to manage the restitution programme has been highlighted, including by several judicial outcomes. The same thing has happened to the failure of the state to administer the “post-settlement” process for people who have received land as part of the restitution programme.

This is what should now be called out: the institutional incompetence, the administrative lethargy, the policy confusion. Our collective future is at stake. What has now added to the general crisis of landlessness is the catastrophic failure of imagination — the failure to envision a new policy direction. Excuses about the legal and constitutional framework no longer have any credibility. The Constitution is the mandate for transformation of land relations.

Read the first part here: https://thoughtleader.co.za/land-slavery-and-cattle-matter-to-move-forward-we-need-to-look-back/