In a previous incarnation (what seems like a lifetime ago in a distant land) I worked as a journalist; as a reporter, a news photographer, a sub-editor and then as a political correspondent. The brief period that I worked as a news photographer coincided, loosely, with some of the darkest days of the late apartheid period.

It was the mid-1980s. Everyone lived in fear. Our lives were filled with clouds of smoke, the acrid smell of teargas or cordite, the sounds of crying, the pounding defiant thump of the toyi-toyi, and the demonic drones of incoming equites in their Casspir stallions. It was a time of unbelievable silence and noise, stillness and chaos, waiting and longing and expecting and death and dying. Yet, somewhere, somehow, in the midst of it all, in between the utter despair and the sounds of crying, there was hope. The one thing we did have — and clung to — had a name. Mandela!

Not many of us knew what he looked like, or what he stood for. His face could not be displayed and his words were banned. It was to Mandela we pinned our hopes. It was not that he would come and save us in some supernatural or sacerdotal wave of hand. He stood more, I seem to recall, as a symbol, or a type of arch (of triumph?) through which we would, someday, travel to reach our promise land. We were rather optimistic, then. How foolish of us. There is some irony in the fact that a priest once told me, in February 1989, that the street children in his church dormitories (in Salvador, Brazil) had no such hope; they did not have a Mandela, he said. We did, he said.

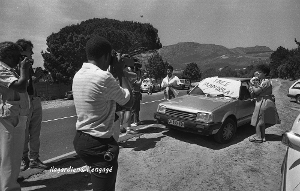

Anyway, in my incarnation as a news photographer, when he was in prison, I stalked him like a predator. Like everyone else in the pack, I wanted the picture of him walking out of prison, a free person. I did not stalk only him, I also stalked the people who stalked him; those who held vigils and staked their lives and livelihoods on him. As it goes, I wasn’t there when he did walk free. I was back in the newsroom assisting with the editing of the next day’s paper which carried his release. As he lays dying, now (can there be any doubt?), he is being stalked again. The predatory behaviour of the news photographer is on full display, again.

But for Mandela himself, actually, I may, today, still be running with the pack. It was Mandela who first asked me to join his government in 1994 (I did, briefly, in 1995, before returning to graduate school). I drifted away from news media since then, and entered academia. As for photography, I have become more interested in the philosophy of the image, and in photographs as mnemonic devices. And so I come to the picture, above, scanned from old negatives of the time when I, too, was part of the pack of news photographers. Arguably, the most predatory of voyeurs in our social world; we purposefully seek out things to photograph. It is in our interest that things (good or bad; bad usually sells more newspapers) happen. And when we’re done making pictures we seek out another crisis, another tragedy, another war, another child whom we dress in our image of poverty, misery and suffering — then claim objectivity.

The picture serves as a reminder, at least to me, of how this man, Nelson Mandela, has been stalked from captivity through freedom and now, as he approaches death, the pack is gathering, again. It’s what we do.