Once I was a girl, then I was somewhere in between, and now I am an adult woman.

What that means for me is not the same as it is for other women. We can know our similarities and differences, but we cannot know any other life as intimately and honestly as we know our own. I know that some women’s lives are better than my own, and that some are worse.

We women do know though that our identity is rarely in stasis for more than a second, and we are both held back by the limits of our lives and overwhelmed by their potential. To be a woman is to live a life bipolar.

When I say that I wake up with a sense of pressure on my chest, I am not sure if this is how other women feel. I live in a country where at least one woman is raped every four minutes. This number has not decreased significantly since the new Sexual Offences Act was passed in 2007. At breakfast this morning I told another woman about the extent of violence against women in my country and she began to cry. I wonder if I have been irreparably hardened by always knowing this violence, and having adapted to its reality.

It seems obvious then that I wake up with a sense that I am in danger, and that this feeling is likely not shared by the men in my country. I wake up in a world that is hostile to my very success – a world that resents it when I thrive and that moves swiftly to address any idea I might have that I am equal or can make choices about my clothing, or who I love.

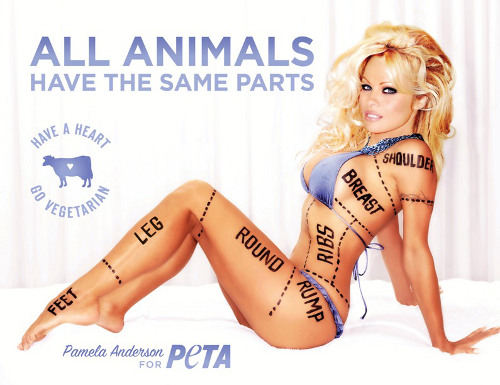

This is reiterated to me daily in my observation of advertising that objectifies me slice by slice, limb by limb. It can be observed in the way that male politicians berate female politicians as though they were children, or insult their bodies rather than tackle their arguments. I witness it each year in the statistics that say that women are the most likely victims of sexual assault and rape, and in the failure of society to recognise that these are not individual acts but a systemic oppression of women’s freedom. Even the police don’t fear the law, 37 of them are facing charges for rape. I have not been raped and I have not been the victim of sexual assault, but I wake up with the pressure on my chest telling me that it is likely that my time will come, and if I am surprised by it then I am just naïve.

Simultaneously I live in a world that tells me I can do more than any women who came before my generation. I live in a country where the representation of women in government is high and where I have laws that protect my right to an abortion, to divorce, to employment opportunities, to own property, to drive. Not only can I vote, but I can also run for office. I could be president one day, in theory.

The women in my life all feel powerful to me. They are independent, brave, outspoken, sexually liberated, and articulate. Yet, we all know that when we walk down a street our internal discussions about our rights to wear our short skirt may be drowned out by wolf whistles, kissing sounds, or “hello baby, you look nice today nuh lady, give me a smile”. Some of us may die during childbirth, or our children may die shortly after. We will not meet millennium development goal 5.

Our youth literacy rates show that girls are as literate as boys, and that more women enroll in university than men. We have women doctors, scientists, Nobel peace prize winners, humanitarians, writers, politicians and leaders. A little girl in my country should not have to imagine that her life will depend on a man.

But it is likely that it will, and it is likely that that man will beat her. In 2011, almost 220 000 incidents of domestic violence were reported in my country. When the number of sexual offences reported are compared to the number of convictions made, the percentage of rapists that go to jail is four. Four out of 100 rapists in jail, 96 free. This is truly a terrifying statistic, when we know that most men who say that they have raped have done it more than once. Even those who have survived war and genocide in their own countries may be unsafe in my own.

Most women who are murdered in South Africa, are murdered by their intimate partner. Reeva Steenkamp is not an exceptional case and sadly it is only because of the fame of her murderer that we hear anything about her at all. We do not currently face the threat of external terrorism in South Africa – for women the terrorism comes from within our homes, communities, schools and workplaces.

My mother left my father when I was very young. She didn’t have any university education but has worked her way up through the ranks to be a leader in her industry. She did this while financing two young and determined girls through school and university. She could leave because our laws protected her right to leave and her right to maintenance. My sister and I could succeed because our mother raised us to believe that the world was our oyster and we owed it to ourselves to be successful. My aunt has travelled the world, owns her own property, and has done this on her own purse strings. I am one of a family of brave and courageous women and next year I will inherit another such family when I marry my fiancé. The message I receive from them all is to be both loving and fearless.

But I do fear. A few nights ago some women and I walked to the shops in Uganda after a day of writing and political discussion. When it came time to leave the shops, night had fallen. There were few streetlights on our journey home and at some points we walked together in pitch darkness. I felt the familiar feeling of a thudding chest, racing heart, and hyper-vigilance.

I do not often have to walk home in the dark, something that at home I am grateful for. I know a night under South African stars means danger for most women. When we reached our hotel safely, without so much as a comment from any men we walked past, it was difficult to control a sense that women are being cheated in my country. I am being starved of the opportunity to walk freely with other women at night by a failure to address norms that say that men own it and own us.

The other day a workshop participant said just because we plant a tree, does not necessarily mean that we will be able to sit in its shade in our lifetimes. I also know that exotic trees tend to grow faster than indigenous ones. So if as many would have us believe, women’s rights and feminisms are un-African, perhaps that shade will be around sooner than we think. But I know in my heart that women’s activism is indigenous, and so it may be slow, but it will result in benefits for generations to come. What is important is that we keep planting those seeds, and nourish the seeds that our foremothers have already planted.

A poem we read this week said “we are the tomorrows our grandmothers dreamed about”. I hope that by the time I am a grandmother, my dreams for my granddaughters will be simpler, less urgent. I hope that when they wake up one day as women it is with a sense of lightness, of hope, and of freedom.

This work was developed during the African Women’s Development Fund and Femrite African Women Creative Non-Fiction Writing Workshop in Uganda, July 2014.

This post originally appeared on Medium, here