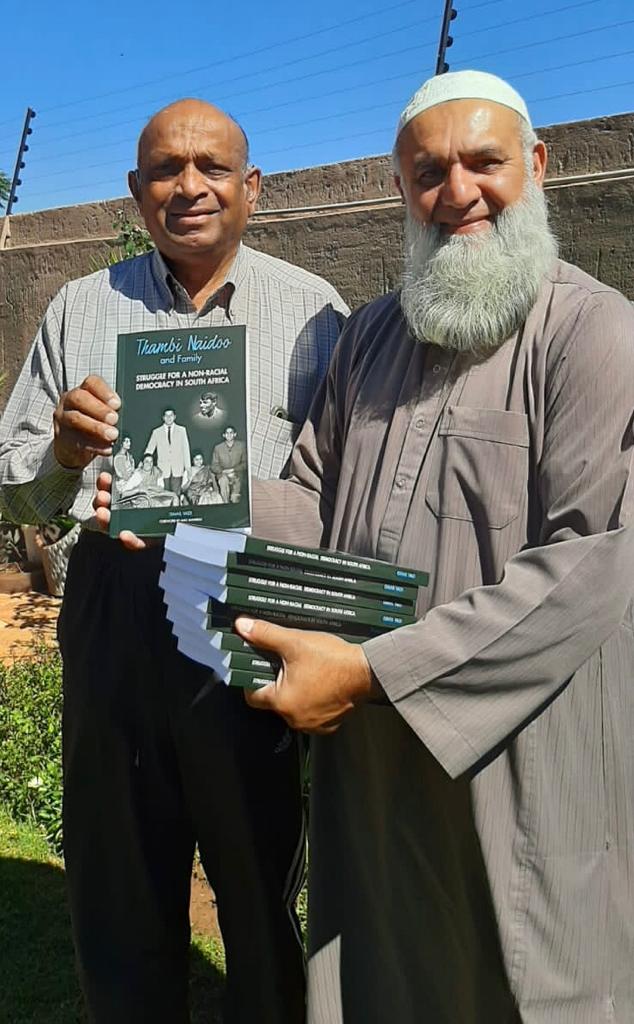

Dr Ismail Vadi has released his latest book, Thambi Naidoo and Family: Struggle for a Non-racial South Africa, which centres on a remarkable family who fought against colonialism and apartheid for four generations. The Naidoo family’s activism dates back to the days of Indian indenture in South Africa, with links to Mahatma Gandhi, and continues today. It highlights the role of the Naidoo women as well as the lineage of the stalwarts such as Ama Naidoo, her son Indres and daughter, Shanthie.

Luli Callinicos, author of Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Engeli Mountains and a fellow comrade, wrote the prologue:

I first met the Naidoo family in 1958. Intrigued by the radical weekly newspaper, New Age, sold by youngsters on street corners, my pharmacist partner and I decided to support the paper by placing advertisements for our “famous”cough mixture. This was followed soon afterwards by a visit from the editor of the paper, Ivan Schermbrucker and Ben Turok,

Secretary of the Congress of Democrats (COD), the small white wing of the African National Congress alliance. It was a visit that irrevocably changed my life.

Visiting the COD office soon afterwards, I met Shanthie Naidoo, who worked there. We became lifelong friends. I was soon invited to visit Shanthie’s family home in Doornfontein for a vegetarian meal and met her warm and hospitable mother, “Ama”, and her brother Indres. Little did I know at the time, Ama was an honourable activist in her own right, widow of trade unionist “Roy” Naidoo, who was a member of an esteemed family. A generation earlier Mahatma Gandhi and his supporter, Thambi Naidoo, were to inspire the oppressed Indian community, women and children as well as men, to resist injustice and discrimination through the brilliant tactic of Passive Resistance.

It was the Naidoo family who introduced me to the real world of non-racial, anti-apartheid activism and the dream of social and economic equality and democracy for South Africa. I was one of many young people of all shades who found encouragement and political education in the home of the Naidoos. Their influence went far beyond their inclusive

hospitality. Their humanistic yet radical activism and preparedness to make sacrifices to reach their ideal had a profound influence on all who were drawn to this remarkable family.

The narrative in this highly readable book unfolds through four generations of two intertwined families of Naidoos and Pillays. The founding father, Thambi Naidoo, was the exemplar of service to the community, willing to sacrifice his material interests and even draw in all the members of his family to serve the noble cause of dignity and social justice. This legacy of dedication to serve, ultimately led to an inclusive sense of humanity, regardless of race and class, contributing significantly towards a concept of a complete South African nation.

This biography reveals how each generation of the Naidoos, and to some extent the Pillays, learned and drew from the exemplars who came before them. Over more than a century, as their hard and consistent struggle intensified, they were persecuted, tortured, imprisoned. Their lives were cut short and the health of some suffered throughout their lives. Yet, consistently, the legacy of the descendants of Thambi Naidoo upheld his staunch dedication to democracy. His remarkable example and values inspired the descendants who followed, as well as a large proportion of the Indian community.

RELATED:

Ismail Vadi is ideally placed to have recorded this remarkable story; he is an historian and intellectual deeply involved in the politics of the Indian community and is himself an active contributor to the unfolding of events in his lifetime. In this book, he reveals how the post-apartheid generation did not relax the family vision; they consistently continued

to serve the nation in their thoughtfully chosen fields. From generation to generation, they prepared themselves, through a proud tradition, strength of character and purpose, to contribute to the welfare of an inclusive national good.

He draws the reader to discover how each generation passed on to the next these historic values. One learns how the descendants of the successive Naidoos chose their paths. And how over the generations, progressives in the Indian community partnered with the African National Congress in the 1940s, through non-racial organisations such as the Communist Party of South Africa, the trade unions and the civic movements.

The South African Indian Congress was central to the formation of the Congress Alliance in the 1950s, and in the following generations, along with the other Congress movements, was to play a substantial role in South Africa’s struggle for democracy and equality.

I recommend this inspiring story of commitment and service to all those who strive for a non-racial, inclusive and democratic South Africa.

A message from the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, which published the book, was written by the chairperson of its Board of Trustees, Derek Hanekom:

In the foreword to Indres Naidoo’s book, Island in Chains, Mac Maharaj writes: “The quality of what we bequeath to posterity will in part be determined by our willingness to understand others who are destined to be part of the South African nation. There will be no better time than now for the storytellers from every walk of life in our country and continent to tell their stories so that we may better understand the experiences which have shaped them; so that we may know them, and thereby better know ourselves.”

Writing about the “terrorist album” that was a security police’s collection of pictures of more than 8 000 “terrorists against the apartheid state”, Jacob Dlamini states: “Viewed from the vantage point of the 21st century, there is a sense in which the album — with its collection of black and white, young and old, liberal and radical — offers against itself and its compilers a collective portrait of hope and idealism that animated the anti-apartheid movement of the 20th century. To look at the album from this vantage point is not to see the omniscience of the apartheid state, with its neat framing of dissidence, but the hopeless failure of that

state to stave off its demise. Read against itself, the album offers a vivid portrait of a cosmopolitan and democratic vision for South Africa. This raises the question of how a state that defined itself as White supremacy’s last hope in Africa dealt with opposition that came not in the predictable black but in a rainbow of colours. How, in words, did the album handle the question of race when opponents of apartheid’s thinking about race came in so many colours?”

There was nothing inevitable about the end of apartheid. It took years of struggle by millions of people, including those captured in the album, to bring apartheid to its knees.

This book features many who would have been in different “terrorist” albums of the colonial and apartheid state. The remarkable part of this story is that it is one that tells the story of resistance over four generations. Through the story of the Naidoo family, we get an enriched

understanding of how generations contributed to the ending of apartheid and the rebuilding of South Africa.

This book by Ismail Vadi is indicative of the type of history that needs to be written in South Africa. Work that locates the contributions of ordinary people doing extraordinary things to bring down an unjust system. Ahmed Kathrada’s preface to an unpublished manuscript,

“Centurions of the Struggle”, could very well have been written for this book on the Naidoo family when he said: “This book is dedicated to the countless unsung heroes whose identities remain unknown. They were the tens of thousands of women, men and children in their workplace, in their homes, and in schools and universities whose contributions and sacrifices on the road to freedom were of immense significance. They will forever be remembered with gratitude and pride.

RELATED:

History is often presented as being made by “big men”. There is a need to refute and challenge this notion as in the South African struggle for national liberation literally hundreds of thousands of men and women participated actively. The Kathrada Foundation extends its gratitude to the Naidoo family for their collaboration in making this project possible and for sharing their story with many others, who might be inspired to undertake similar projects on behalf of their families.