Charlotte Mannya Maxeke took the unusual step in 1902 to insist on the participation of women in church and political meetings. She had graduated with a BSc degree in 1901, becoming the first indigenous South African woman to achieve this. When she returned home from Ohio in the United States, she found herself stuck in the Cape as the country was plunged in the Anglo-Boer War.

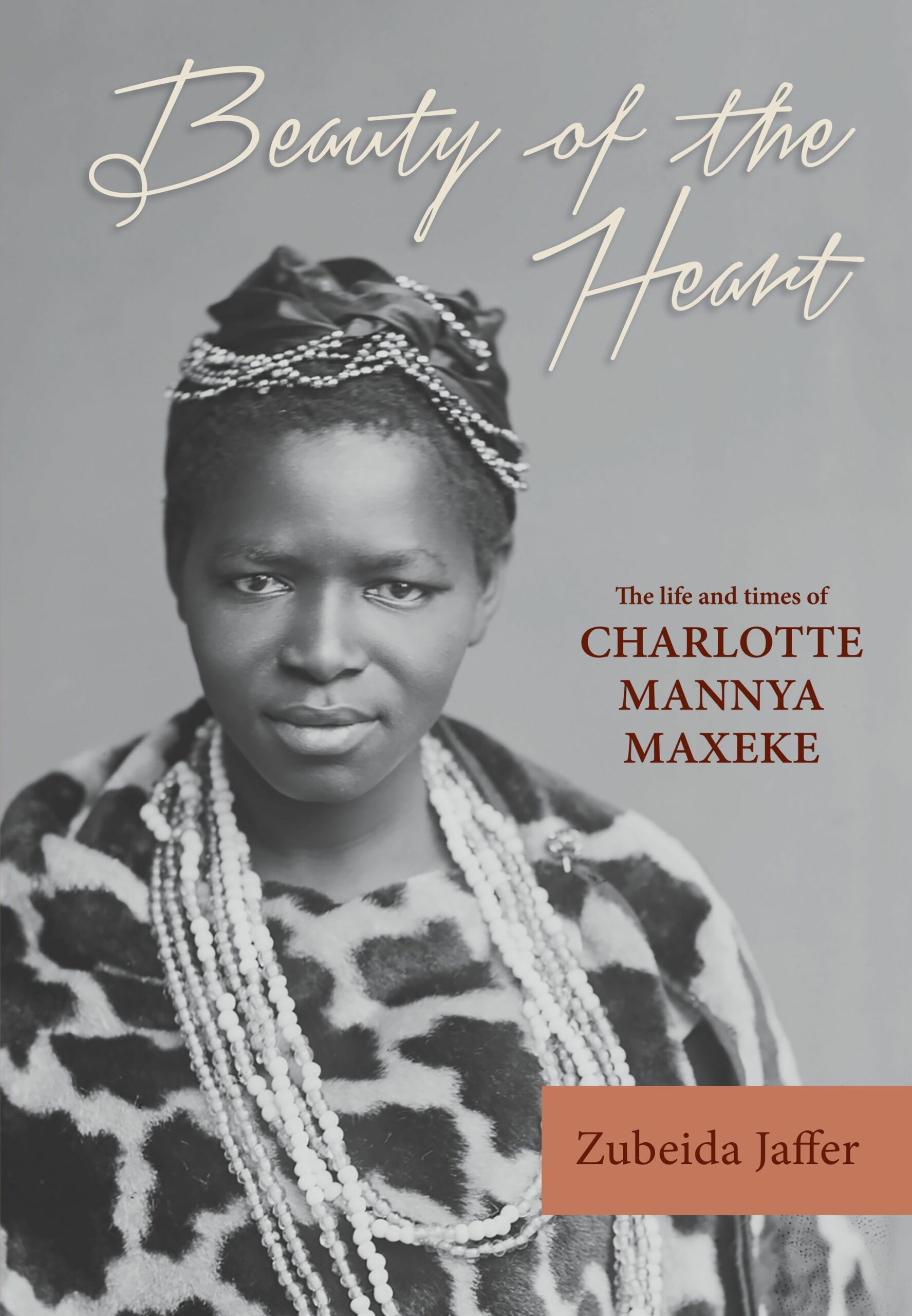

Her plan was to travel to Ramokgopa village near what is today Polokwane to join her father and start her dream of educating the local people. Nearly eight years had passed since she had last seen her family in 1894 and in that time her mother had died. It must have been with a heavy heart that she waited in the Cape for the war to end. The details of her life’s trajectory are recorded in my book, Beauty of the Heart: The Life and Times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke.

At last, in mid-1902, Maxeke could finally make the journey north to what is now the province of Limpopo. En route she took her first active steps in organised politics at home when she attended the annual meeting of the South African Native Convention or Ingqungqutela in Queenstown. This Cape-based organisation, formed in 1890, was the early manifestation of efforts to establish the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) 20 years later.

She must have had some inkling that arriving at this meeting would cause controversy. In October that year she joined the gathering of delegates who came from King William’s Town, Queenstown, Engcobo, All Saints, Herschel, St Marks, Macibini, Mkubiso, Peelton, Somerset East, Kobonqala, Bedford, Emncontsho, Sihobothini, Glen Grey, Oxkrall, Cala and the Transvaal. The convenor and chairperson was Thomas Mqanda, the secretary was Jonathan Tunyiswa and the assistant secretary was Reverend Stephen Mdliva. The place where they gathered was 10km north of Queenstown known as Lesseyton at the base of the Hengklip Mountain where the Tembu lived.

Church members at the Lesseyton Methodist Church of South Africa are now gearing up to prepare the site as part of the Charlotte Mannya Maxeke Heritage Trail. The church has initiated a heritage project to restore the site and record the history of the Lesseyton Methodist Mission Station. This was a place where Maxeke subsequently attended several meetings.

On that day, she was the only woman present and said she needed clarity on the purpose of the congress and its objectives. She also asked if it was possible to have women forming part of the congress. As a result, a committee was nominated to respond to her. She had firmly placed the matter on the agenda and must have waited eagerly for the outcome. The committee tabled the matter and replied by saying the time was not yet ripe for women to lead delegations let alone take part in civil movements. It further said it was advisable for women to form their own movements.

There is no record that tells us how she reacted to this decision. What is interesting is at least one man publicly expressed his point of view on the matter. Journalist Sol Plaatje was outraged and put pen to paper. In an article in Koranta ea Becoana, he said that this decision reflected an imitation of whites that exclude women from their public forums.

“What was the state of affairs at the convention? Out of a gathering of 40 robust masculine men not one could boast of even a Kaffrarian degree, while Miss Charlotte, who was refused admittance on account of her sex, is, besides other attainments, a BSc of an American university and in a report covering more than nine columns of the Izwi, hers was the neatest and most sensible little speech …

“We are great believers in classification, you know, but classifications of the right kind, not discrimination and just as strongly as we object to the line of demarcation being drawn on the basis of a person’s colour, so we abhor disqualification founded on a person’s sex. The convention would surely have benefited by the experience of one, who though a woman, is not only their intellectual superior, but is besides leading an adventurous missionary life among the heathens of the Zoutpansberg, while they demonstrate their manliness by leisurely enjoying the sea breeze at the coast.”

Not only do these words indicate the high esteem with which he held Charlotte, but they also show how advanced Plaatje, the first general secretary of the SANNC, and others were in their social analyses. He rejected discrimination on the basis of colour and sex, accepting Maxeke as his equal. In this, they both stood head and shoulders above other progressives at home and around the world. The movement for women’s equality was stumbling along and struggling to gain momentum locally and internationally. It was still a long way from 1994 when all South Africans got the vote. These ideas had been fully embraced by some of the early intellectuals. These were ideas and rights that are now in the constitution of our democracy.

And who was one of the trailblazers? Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, whose 150th birthday celebration takes place on 7 April. Her stand in 1902 paved the way for her becoming the only woman present at the formation of the ANC in 1912 — she was not excluded from the meeting.

Despite her boldness, she was written out of history and her name largely erased from collective memory as a colonial and apartheid narrative gained ascendency holding all of us in its pincer-like grip.