Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, with customary forthrightness, recently broke ranks with his own church to plead for a “mind shift” in the “right to die” debate.

“I think when you need machines to help you breathe then you have to ask questions about the quality of life being experienced … Why is a life that is ending being prolonged? … Money should be spent on those that are at the beginning or in full flow of their life.”

Unfortunately the reality is, as Tutu is undoubtedly aware, that there are not many “good” ways to die, once you reach your 90s.

A farmer I know of was dragging logs when he flipped the tractor, to be found hours later crushed to death. That’s horrific but as good a death as one can reasonably hope for at 93. Alone, sure. But still active, dying under an open sky with his cheek nestled to the veld that he loved.

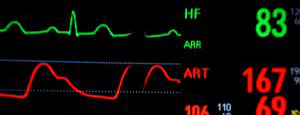

Perversely, it’s the very excellence of modern medicine that often makes death cloistered, protracted and traumatic. The drugs list lengthens; pipes and tubes proliferate, cratering paper-thin skin; and the respirator imposes its arbitrary cadence over the most rarely contemplated aspect of our existence — the infinitely varied and subtle rhythm of our breathing.

Meanwhile bedpans and catheters and blood scrubbers steadily strip the elderly of the dignity afforded by choice. Soon that unique individual we treasured, a loveable jumble of idiosyncrasies and foibles, of kindnesses and convictions, is little more than a machine-processed distillation, personality transformed to pap. Alive but not living.

The tortures endured by the fading geriatric are the result of an unholy conjunction of gods both ancient and modern. Not only does the physicians’ Hippocratic pledge to Apollo enjoin them to do no harm, but their every professionally honed instinct is to prolong life. Toss in the Judaeo-Christian legal strictures against assisted death. Then finally add the deity of choice in private healthcare, Mammon, who echoes the refrain “keep ‘em alive at any cost”. Well, at least until their medical aid reserves are exhausted.

Despite the life instinct, the fierce determination that causes us, in the words of Dylan Thomas, “to rage, rage against the dying of the light”, none of us wants an agonising and prolonged swansong. That the exit be instantaneous or accompanied at worst by fleeting pain, is everyone’s death wish.

Sadly, most of the elderly are not taken swiftly. Like love, death can stalk and torment. It dances enticingly close and then, vowing teasingly to return soon to end the misery, it swirls away to tarry with another.

Our mother, known always as Vossie, from her maiden name Vosloo, was unambiguous about terminal anguish: “Rather just shoot me.” A blunt view rooted, I suspect, in the unsentimental reality of a Free State farming childhood during the Depression.

Mom was a remarkably healthy nonagenarian, free of chronic illness. She lived in her own home, conveniently close to her formidably competent physician of almost 40 years. Age irked but did not conquer. The mental gears slipped on occasion, but there was traction aplenty for crosswords, to interrogate current affairs, or to lament the fickle fortunes of her favourite rugby team.

About a year ago she grudgingly conceded to 24-hour care, but the women were social companions as much as aides. Her routine revolved around pottering about her domain; caring for her dog and cats; and indulging wickedly the whims of the live-in carer’s toddler. On Thursdays she sallied forth for a perm-and-set and on Saturdays she would lunch — including a gin-and-tonic and couple of glasses of wine — at the home of a trio of dear friends.

Nevertheless, when she fell and broke a hip, we all knew the prognosis at age 92 was not good. She had dreaded this. Her own mother had broken her hip at 96 and although she eked out two more years, Ouma’s precipitous mental and physical decline was distressing for everyone, including herself.

Mom had also already had to do fierce battle. In her mid-80s that same leg had been shredded terribly in a road accident. Not only had she stoically endured many months of painful rehabilitation but she had also confounded medical opinion by walking again. Unaided.

This time it was different. Overwhelmed by post-operative pain, she drifted in and out of lucidity. In such a moment, in response to my assurance that she would recover, although it would entail a long battle, she shook her head. “No, I don’t think so,” she whispered ambiguously and then still holding my hand, drifted away again.

Mom was weak, eating with reluctance, but the medical imperative is to get patients ambulatory as quickly as is possible. Within days she was in the rehabilitation ward with its necessarily punishing regimes, and nurses with less time and inclination to win the co-operation of an obdurate old woman.

The interventionist medicine that she had always feared suddenly took over: Lung drains, a feeding tube, and an oxygen mask. Her hands were tied to the sides of the bed. That mean that she now could no longer claw at the hated lines as she had tried to do, but nor could she any longer scratch an itch.

On the Saturday morning, tearful but quietly coherent, she firmly made clear it was enough. She wanted to be with her animals, in her own bed, in her own home.

No can do, said the hospital. Discharges only on weekdays. Eventually a legally fraught “refused hospital treatment” waiver was signed and within hours she was home.

She was made comfortable and on that Sunday at 23.15pm she died, her favourite cat settled beside her on the other pillow. It was over. Not a “good” way of dying, but until laws and attitudes change, as good a death as Vossie and those who loved her could have hoped for.

There was a bizarre post-script. Because hospital treatment had been refused, there was the spectre of inflicting on mom’s life-battered body the final indignities of a forensic post-mortem. Eventually good sense and humanity prevailed and the cremation took place as scheduled.

This is not the story of just one mother. It’s the story of what happens to many aged or terminally-ill South Africans, to their distress and the distress of their loved ones. When someone of sound mind calls out to death, it’s time that physicians and lawmakers summoned the empathy to make gentle that last embrace.

Or as that old medico-legal warhorse Prof SA Strauss, a passionate advocate of the “living will” and the right to end a life not worth living puts it, there is a thin line between “medical care” and “medical cruelty”.

Follow WSM on Twitter @TheJaundicedEye