During the global Covid-19 pandemic, we have seen a great deal of resilience in the face of adversity. Locally, non-profit organisations and volunteer efforts came together to meet the needs of communities in distress.

Although volunteer and non-profit organisations’ efforts reveal a great deal about citizens’ generosity, resilience and humanity, South Africa’s democratically elected leaders as well as assorted civil servants and entrepreneurs undermined these efforts as scandals about stolen Covid-19 relief funds, questionable UIF payments, government pension funds being used to prop up media entities, and irregular tenders come to light.

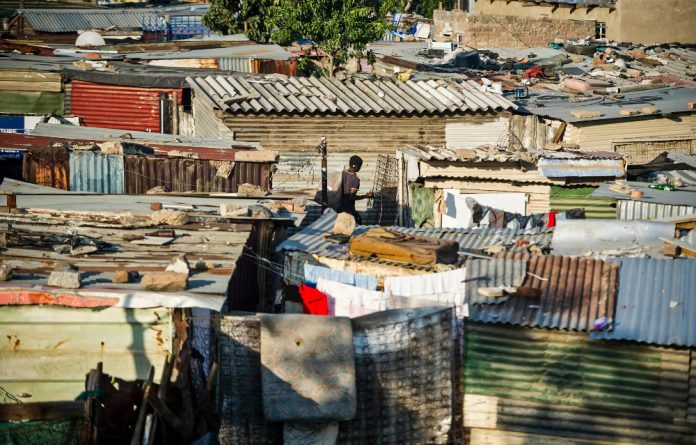

One might say that these two contradictory efforts – one to assist vulnerable communities and the other to prey off them – tell us a great deal about South Africa’s heritage. Having survived a few hundred years of predation during colonialism and 48 years of legislated apartheid, our cultures of struggle against injustice have become a key aspect of our heritage. It has not been erased, in much the same way that we have kept our multilingual songs of happiness and resistance alive.

At the same time, the predatory practices of “tenderpreneurs”, especially in the midst of a global humanitarian crisis, tells us that cultures of predation appear to be a key part of our heritage as well.

This is not unlike the culture of violence at the hands of the South African Police Service (SAPS) on the scene of many a service delivery protest – or a protest against gender-based violence (GBV), for that matter.

The killing of the mentally disabled teen Nathaniel Julius in Eldorado Park is yet another tragic instance of this entrenched violence. One can hardly tell the difference between the violence of our police during or after the fall of apartheid.

Violence thus appears to be a key part of our heritage as well – be it the violence of SAPS, evictions during the lockdown, the violence of stealing public funds or GBV, along with perceived police inaction.

Call it a dual heritage: one of both resilience and predation.

What is to be done, though?

If we are to preserve only the positive aspects of our dual heritage, we need to ensure that we do more than treat symptoms. Charity, philanthropy or media campaigns that scratch the surface hardly address the root causes of South Africa’s predatory heritage. For example, if we are going to address GBV, we need to educate citizens and public officials about misogyny, homophobia and patriarchy. We need to empower law enforcement as well as educators, social workers, occupational therapists, gender activists and psychologists to address the underlying causes of GBV.

This is not merely an issue for SAPS and the National Prosecuting Authority to address. A broader set of stakeholders need to join heads to develop a coordinated strategy to address violent crime, toxic masculinity and GBV. This includes interrogating the institutional culture of SAPS. In other words, we need a systemic approach to a systemic problem.

As for the violence of corruption and the callousness of the predatory elite, we need to take a critical look at the neoliberal economic environment in which both public services are delivered and market actors engage parastatals and citizens, in general. We need to interrogate often uncritical assumptions that adopting corporate models of governance in the provision of services to citizens in a democracy automatically equates with good governance.

Corporate models of governance operate on market principles that are geared towards generating profits. Surely there are models of governance that place people first?

Add to this the issue of corporate monopolies: are we doing enough to prevent anticompetitive, monopolist practices? For example, what would community media and the unsolved challenge of media diversity look like if we prevented corporate monopolies from owning community newspapers – especially when we already know that free knock-and-drop community newspapers have made a killing from advertising? Those free newspapers that are stuffed in your letterboxes are jam-packed with advertising material. What if that advertising revenue went to actual community-owned media entities?

What would journalism look like if government told corporations to stay in their lane? What kind of news would be covered then? What kind of heritage would be captured and preserved if media practitioners served the actual communities to which they belong, and not shareholders and oligarchs?

Add another layer: are we doing enough to tax large corporations and elites?

With all of this talk about the minimum wage, should there not also be a maximum wage? Ethically speaking, should we cap salaries in the face of glaring class inequalities, which are largely racialised? Recently, we read about the chief executive of a large media company being paid R246-million while some of its titles are being shut down and jobs are being lost. The optics are not good at all, but who holds these decision-makers accountable?

Advocates of media freedom would agree that state meddling in the newsroom is unconstitutional, but how about state intervention at the level of the market to ensure meaningful media diversity and to ensure that wealth that is generated gets distributed fairly?

Do the Competition Commission and Media Development and Diversity Agency have sufficient leverage to address this issue, or do we need legislative intervention to create market and labour conditions that are fair and, therefore, actually promote diverse media ownership? Clearly, the state is not doing enough to address the ways in which the market both undermines media freedom and gives the lie to the promise of “trickle down” made by free market fundamentalists.

It is time to end cultures of predation by changing the systems that enable them and to do all that we can to nurture our proud heritage of resilience.

Adam Haupt is professor of media studies at the University of Cape Town