By Athambile Masola

As a language teacher, I have been following the furore about African languages being axed from schools with great interest. I have been reading and trying not to be cynical about every new article announcing that yet another school will no longer offer isiZulu or isiXhosa in the foundation phase. There have been interesting comments made on this topic which I find hackneyed, and it is an issue we really need to stop evading in this country. Why are we surprised that African languages are being marginalised in South Africa, especially in our classrooms?

Seeing as there are distinct systems of education in this country — one for the rich and one for the poor — there are different arguments for teaching African languages (other than Afrikaans, for example, isiXhosa or isiZulu) depending on the system of education learners are in.

If learners are in the privileged sector, African languages are usually taught within a context where English or Afrikaans are the main languages of learning in a school (often they are not introduced until learners are in grade four and the teaching is often at a conversational level). African languages are easily sidelined because parents (regardless of race) do not view an African language as important for their children because they are preparing them for a middle-class world that is saturated with English as the dominant language. This sector perpetuates the idea that African languages are not important, unless for recreational purposes like saying hello to the car guard or the petrol attendant.

In the education system for the poor, African languages are taught as the main language of learning in the foundation phase until grade three. Learners are expected to learn in English from grade four onwards. An African language is usually the mother tongue of the learners in this system of education. The argument here is that learning is beneficial for learners because they are being taught in their mother tongue.

However, this is not the case. Learners in this section of the education system continue failing not because they are not smart enough, or that their mother tongue is disadvantaging them from learning any further, but because the education of the poor child from a poor home and community in this country is in jeopardy. The language debate often gets conflated in trying to understand the failure rates of learners in schools where African languages are the primary languages for the classroom.

The curriculum suggests that schools have to introduce English from grade one in addition to another language, Afrikaans or isiXhosa/isiZulu/SiSwati etc. The toss-up is whether to introduce Afrikaans or another African language as the additional language. Most schools are opting for Afrikaans. There are many complex reasons here, the obvious one being that Afrikaans has maintained social capital because it has the resources and intellectual support to keep developing whereas many African languages remain marginalised. This suggests that there’s no place for African languages (other than Afrikaans, because I do consider Afrikaans an African language) in the school system and beyond the classroom.

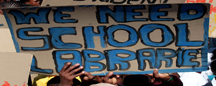

The uproar shouldn’t surprise us because it speaks to the disparity in our education system where privileged learners are in the English stream of education and poorer learners are not. The use of African languages in the school system should be everyone’s problem, not only parents whose children speak African languages as their mother tongue. The dominance of English has implications for the use of marginalised African languages, especially when there is a lack of support for quality teaching in these languages.

The Constitution recognises the need to protect language rights in this country. However, the education system and the schools in this country seem to reflect a different reality. I wouldn’t be surprised if the next curriculum shift pertaining to language (especially for the foundation phase) suggests an English-only approach because of the shortage of teachers in the foundation phase who are able to teach in English and an African language (that is not Afrikaans).

Once again, challenges regarding the language of teaching in our education system have come to the fore. The choice for the language of teaching in schools is in the hands of school governing bodies but have curriculum planners considered what this really means in light of the unequal system of education in South Africa?

The important questions that should be considered are the implications that this will have for the future of this country and our ability to communicate in spite of our language diversity. Will this diversity still exist in 50 years’ time? What is the role of education in ensuring that African languages are protected and continue to be used? The language debate has implications for not only our personal identities as people but it also has meaning for the national question of difference and diversity and the role of language in our daily interactions.

Athambile Masola is a teacher at a high school in Cape Town.