Liminality is a strange phenomenon: The Encarta dictionary online defines it as ‘belonging to the point of conscious awareness below which something cannot be experienced or felt’, which is only one of the ways the term is used, but nevertheless gives a good idea of what is involved when you call something ‘liminal’. The point is that it marks a kind of threshold between domains, which can be of various kinds, and thinkers, writers and artists who explore it are engaging in an unpredictable activity, where both domains in question have an impact on their investigations.

South African artist – I should really say ‘cosmopolitan artist’, given his astonishing international peregrinations – Jonathan Silverman’s art is of such a liminal kind, as anyone who is receptive to the meaning of images would notice when they visit his current exhibition at UCT’s Michaelis Art Galleries in Cape Town (running until March 1), which I had the privilege to open with an ‘official’ (but informal) address yesterday (February 16). It is titled ‘Searching for an Electric Peanut (part II)’, and the oxymoron in the title already intimates its liminality.

South African artist – I should really say ‘cosmopolitan artist’, given his astonishing international peregrinations – Jonathan Silverman’s art is of such a liminal kind, as anyone who is receptive to the meaning of images would notice when they visit his current exhibition at UCT’s Michaelis Art Galleries in Cape Town (running until March 1), which I had the privilege to open with an ‘official’ (but informal) address yesterday (February 16). It is titled ‘Searching for an Electric Peanut (part II)’, and the oxymoron in the title already intimates its liminality.

But that would be mere conceptual prestidigitation, had it not been for the paintings’ traditional, painted images (the ‘Peanut’ part), on the one hand, juxtaposed, and interacting with his video-work (the ‘Electric’ part) on the other. It is the interaction that makes the show so interesting. Succinctly put, viewers are confronted with the fact that they move from one domain (the world of physicality) to the other (that of the digital or virtual) and back while viewing the artworks, and by implication – this should ideally strike everyone – this is an experience that is paradigmatic of our lives in the early 21ste century.

Who can deny that such ambivalence — ‘ontological’ ambivalence, to give it its proper name – characterises life in the realm of the ‘network society’ (Castells), or the era of Empire (Hardt and Negri), and that it is part and parcel of living in an ‘accelerated’ world (Virilio)? Only those who are blind to the difference, and in a sense the irreconcilability, between the two qualitatively divergent experiences alluded to here, would be oblivious of this ambivalence.

Other artists are aware of this too, of course, and it is not surprising to discover in their work similarities with Jonathan’s. One such artist I wrote about here fairly recently is Joy Garnett (see ), who sees her work as being provoked by Virilio’s notion of ‘grey ecology’ — the ‘ecology of distances’ where distance is being overcome by contemporary modes of communication, which tend to diminish time unbearably, so that Virilio perceives a shrinking world, anticipating that it will become uninhabitable because of its lack of spatial ‘distance’.

Garnett’s artistic strategy as a painter is to intervene in the virtualisation of the world, which — like Virilio — she sees as something that alienates us from our originarily embodied experience of the world. She achieves this in her own painting by appropriating digital images of a scientific, documentary or military provenance and ‘remaking’ them in such a way that they become commensurate with natural human needs. In other words, Garnett harnesses her art as a ‘gentle’ weapon to subvert the more damaging effects of ubiquitous ‘acceleration’, in this way reminding one forcibly of a way of living that is consonant with human needs and desires.

Just how this resonates with Jonathan Silverman’s artistic self-understanding is immediately evident from what he observes on his exhibition website (linked above): ‘Our lives are shaped by our connection to physical objects and our digital experiences. Beyond what we are consciously aware of, our interaction with the digital and virtual has a profound effect on our psyche. With its negative and positive implications, it is our inevitable reality.’

To be sure, it would be disingenuous to deny that the ‘virtual’ domain comprising the more valorised aspect of human social experience today (witness the hegemony of social networking sites and applications such as Facebook and Twitter) has ‘positive implications, [and]…is our inevitable reality’, nor that it ‘has a profound effect on our psyche’, as Silverman points out. However, the exhibition in question has the virtue of making one aware of this effect, and although he affirms its ‘positive’ effects, he generously leaves it up to the visitor in this liminal space of the sought-after ‘electric peanut’ to discover for themselves what the virtual’s effects are.

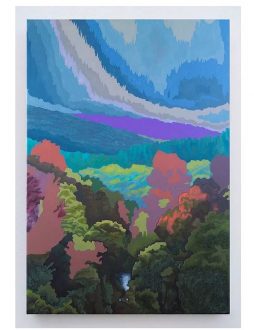

Unfortunately the video is not available on the exhibition site linked above, although there are several video stills that would give one a good idea of what it would be like to see it in kinematic terms. The very first image that comes up, before the painting, ‘Polyphonic dive’ (a metonymy for the exhibition as a whole) — the one where the exhibition title and dates are announced – looks like the opening image of the video (as does the mixed media on canvas work titled ‘Searching for an electric peanut’; there’s an ‘electric sunset’ too). Incidentally, the video has a haunting soundtrack that augments the visual effects in suitably ‘unearthly’ auditory format.

The opening image of the video has a ‘liquid-smoky’ feel about it (another oxymoron!), and resembles the tip of a giant cigarette, minus the cigarette. What makes it unmistakably digital in appearance is the way it contracts and expands – undulates; a light blue, pinkish-orange space, partly surrounded by a dark, predominantly black, cloud-like border, the whole thing pulsating like an electronic planet or sun struggling to be born. This is what digital technology allows the film- or video-maker: to manipulate images as they want to, which Jonathan has done in exemplary fashion here.

There are several images where this becomes particularly apparent. One (number 14 on the website) is based on a photograph (or a still cinematic shot) of two familiar, facing rocks on a Port Elizabeth beach, through the opening between which one can see the ocean, except…in the video the rocks move in a palpitating, tectonic manner. This might seem to be an innocent visual digital experiment, but in fact it is one of the instances of this liminal artistic space where Silverman manages to cross the divide, as it were, between the digital/virtual and the earthy, physical domain indexed by the painted images.

How does he do it? By manipulating the rock-and-sea image, making it palpitate like a rocky heart, it serves as an irresistible reminder of what it is not – it transcends its own ontological character as digital video-art from within, as it were – namely the earth, which is our originary home, Gaia, and her fundamental geological, tectonic structure, visually incarnated in the pulsating, digital rocks.

As one transfers one’s gaze (on the website, and at the exhibition) from one image to the other, it is impossible not to become aware of the textural differences between the video images (and video stills on the website) and the images of oil paintings and mixed media works — the latter have a tactile quality about them which the video images and stills lack. This contrast serves as a telling reminder of the irreducible differences between the digital, virtual domain and the human life-world, where tactility and other markers of our inalienable physicality invite us – as Merleau-Ponty (the phenomenologist of perception) would say – to approach and touch the things that comprise our perceptual horizon.

If you are anywhere near the Gardens area (Orange Street) in Cape Town before the end of the month, do yourself a favour and visit Jonathan Silverman’s ‘Searching for an Electric Peanut (part II)’ at the UCT Michaelis Art Galleries, to confront the divergent spaces of the earthly (and earthy) and the digital, respectively, which are here cannily juxtaposed in an unusual liminal space.