I didn’t really take much notice of the last Zambian election, one which pitted Michael Sata and Rupiah Banda, two men in their 70s.

My lack of interest could have been because I wondered why these men, who actually belong to the nationalist period that swept Africa in the 1960s, should be the ones battling to lead Zambia in the 21st century.

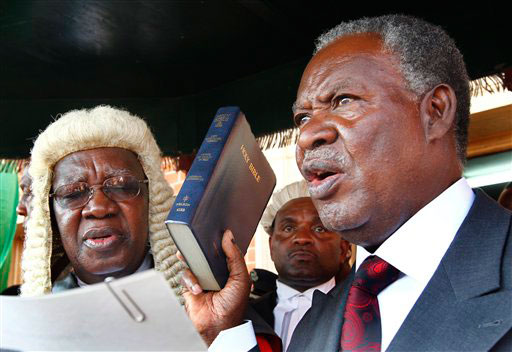

In their last election battle, in 2008, Sata lost to Banda. That election was called after the death of Levy Mwanawasa, president of Zambia from 2002 until his death in August, 2008.

So checking the papers last Sunday, I was surprised to see an article in The Observer whose blurb said “Zambia’s long-standing president stands down after losing an election … a sign that the continent’s fortunes might be changing for the better”.

Long-standing? Wasn’t Banda in office for just three years? My interest pricked, I read further. Banda’s stepping down was described by Ian Birrell as “inspirational”; the writer linked this development to the “remarkable year of uprisings and unpredictable events”. This, presumably, refers to the Arab Spring that brought down Hosni Mubarak, Zinedine ben Ali and Muammar Gaddafi.

“In a continent where all too often presidents cling on to power by any means necessary, Zambia’s Rupiah Banda conceded defeat on Friday with astonishing grace and dignity,” Birrell wrote. Instead of lumping Zambia with Zimbabwe, Kenya and a FEW other countries where the presidents have refused to hand over power, why not actually try to look at Zambia’s own history.

Kenneth Kaunda, the country’s first president, lost an election in 1991 and stepped down. Frederick Chiluba, the diminutive man who defeated Kaunda, stepped down in 2002. To show how strong the country’s institutions are, after leaving office Chiluba was even taken to court to answer corruption charges.

But these particularities get in the way of the “Africa is a doomed continent” narrative. Birrell’s analysis sticks to the tried and tested template of randomly choosing an African country, taking an inconvenient fact about it, and then using it to support an entrenched view, no matter how outdated.

This is, of course, another instance of seeing the continent as one country and refusing to take into account each nation’s individual textures. Sata is going to be Zambia’s fifth president since the country got independence from Britain in 1964. The country’s founding president voted out of power in 1991, still lives in Zambia. Kaunda could have done a Mugabe and refused to step down after the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (on which the Zimbabwe’s Movement for Democratic Change was modelled) trounced his party, United National Independence Party. But he did the right thing and stepped down.

The recent change of power in Zambia, apart from it happening in 2011, has nothing in common with the toppling of the north African dictators. Nothing at all. Zambia has institutions that, although far from perfect, can’t be compared to Egypt, a country that has never had a democratically elected president.

Africa is not a country, you know.