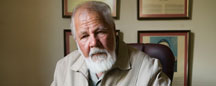

Judge John Horn, who was hearing the murder trial of accused Chris Mahlangu and a minor in the Ventersdorp High Court in North West on Monday, has been asked to rule on the admissibility of the accused’s bail application to form part of the evidence at trial.

The pair is charged with inter alia the murder of former Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging leader Eugene Terre’Blanche during the course of last year.

Mahlangu’s attorney Kgomotso Tlouane has made application to the court to exclude that evidence on the basis that his client had not been aware of the implications of statements he made during his application for bail.

Tlouane said the previous lawyer, Puna Moroko, had not explained the consequences of the statements properly.

Prosecutor George Baloyi, in opposing the application, has argued that Mahlangu had been told of his rights and he had consented to making the statement.

This issue has been dealt with at length by the Constitutional Court in South Africa in S Versus Basson and S Versus Dlamini

While S Versus Basson draws from the decision in Dlamini it should be your starting point.

It confirms that :

“(a) The law as to the admissibility of bail records in criminal proceedings

107. Section 60(11B)(c) of the Criminal Procedure Act provides as follows:

“The record of the bail proceedings … shall form part of the record of the trial of the accused following upon such bail proceedings: Provided that if the accused elects to testify during the course of the bail proceedings the court must inform him or her of the fact that anything he or she says, may be used against him or her at his or her trial and such evidence becomes admissible in any subsequent proceedings.”

However :

“In S v Dlamini; S v Dladla and Others; S v Joubert; S v Schietekat, this Court [Constitutional] held that this provision should not be interpreted to deprive a trial court of its discretion to exclude admissible evidence that would otherwise render the trial unfair. Kriegler J reasoned as follows:

“Provided trial courts remain alert to their duty to exclude evidence that would impair the fairness of the proceedings before them, there can be no risk that evidence unfairly elicited at bail hearings could be used to undermine accused persons’ rights to be tried fairly. It follows that there is no inevitable conflict between s 60(11B)(c) of the CPA and any provision of the Constitution. Subsection (11B)(c) must, of course, be used subject to the accused’s right to a fair trial and the corresponding obligation on the judicial officer presiding at the trial to exclude evidence, the admission of which would render the trial unfair.”

“The Constitutional Court has held that it is the trial court that is best placed to determine what will constitute a fair trial or not.”

The Basson decision then goes on to deal with those instances where the appeal courts might overturn the trial court’s decision.

In a nutshell Judge Horn, taking into consideration the issues presented by both prosecutor and defence, and weighing up the provisions of Section 60 (above) and the constitutional right to a fair trial is deciding whether to exclude or admit the affidavit made by Mahlangu during his bail application.

The stakes are high because if it is admitted Mahlangu cannot give evidence contradictory to that without destroying his credibility. In addition there may well be admissions contained in the bail application which prove the state’s case.

The trial for the murder of the former AWB leader is very high profile and the decisions of the court will make headlines.