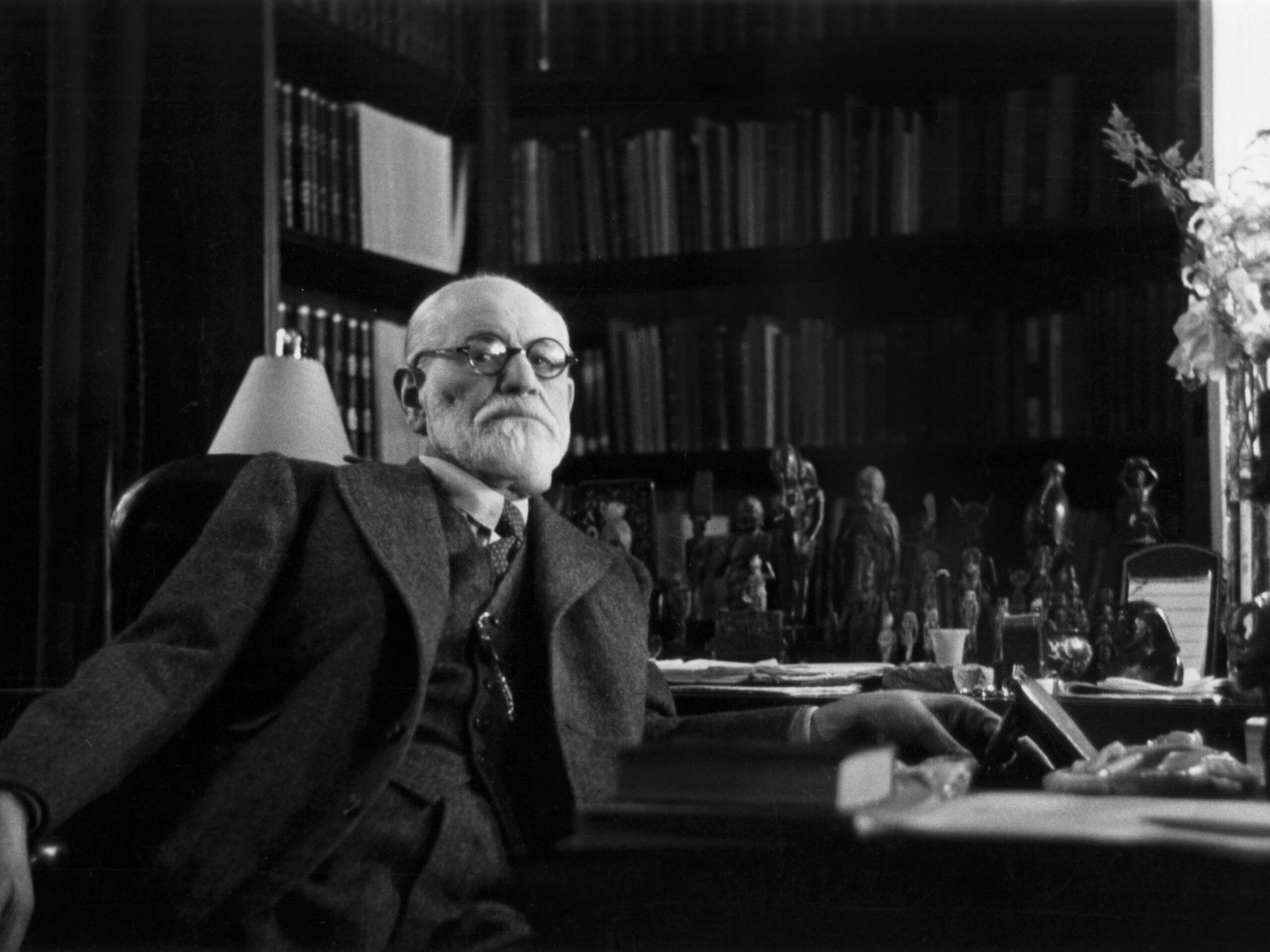

Even for someone who has done his or her best to come to grips with the thought of Sigmund Freud — that is, the many aspects of psychoanalysis, his revolutionary invention — reading Yale law professor Jed Rubenfeld’s two novels, The Interpretation of Murder and The Death Instinct is an adventure in rediscovery of the profundity of Freud’s insights, combined with exhilarating suspense.

The second novel’s title clearly signals Freud’s “presence” in the plot, and I put presence in scare quotes because, as in every appropriation of a thinker’s work, there is interpretation involved — something ambiguously intimated by the title of Rubenfeld’s first novel. He is one of the most intelligent novelists I have read, and judging by the back cover accolades for both books, I am not exceptional in thinking so.

What distinguishes both these novels is that their fictional plots are set against a largely accurately constructed historical backdrop — which is, by itself, not that unusual; there are many so-called historical novels, such as Steven Pressfield‘s astonishing literary reconstruction of the 300 Spartans’ battle at Thermopylae against the massive Persian army, called Gates of Fire, or of the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens, titled Tides of War. What makes Rubenfeld’s novels exceptional, however, is the deft manner in which he weaves Freud’s psychoanalytical theory into his narrative; so much so that they could serve as an introduction to some of Freud’s most important insights — in the context of an exciting, suspenseful narrative, to boot.

As the title suggests, The Interpretation of Murder showcases the capacity of a psychoanalytic approach to unravel human actions in terms of their (unconscious) motives, which here bear upon criminal ones. The action of the story is set against the backdrop of Freud’s visit to the United States in 1909, when he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Clark University and was accompanied by two other psychoanalysts, Sándor Ferenczi and Carl Jung, who was then still regarded as the crown prince of the psychoanalytic movement (before the parricidal break between him and his mentor).

It is fictional, of course, that Freud assisted in solving a case of high-profile murder in Manhattan, New York, through his fictitious American psychoanalyst-colleague, Dr Stratham Younger, and subsequently helped Younger in his attempts to cure another young woman who had been cruelly attacked.

Rubenfeld blends fact and fiction so well in this novel that, had it not been for his Author’s Note at the end — where he scrupulously distinguishes between the two — one might have believed that much of what is described did, in fact, happen, when it did not, and vice versa. Sometimes what the author includes in the book is factual — such as the exchanges between Freud and Jung displaying the grounds of their eventual split, which were all taken from actual correspondence between the two men — while their supposed setting in a hotel in Manhattan is entirely fictional.

It is in these encounters that the fundamental differences between Freud and Jung — soon to disavow Freud’s theory and go his own way — are highlighted, reflecting enormous insight on the part of Rubenfeld, and functioning to enlighten the reader about the grounds of their notorious schism.

In other instances it is not that straightforward to make the distinction between fact and fiction, simply because the historical sources on which certain actions or events in the book are based, are themselves ambiguous. Here I am thinking of Rubenfeld’s depiction of Jung as an inveterate philanderer and anti-Semite, which the author insists is merely a “portrait” based on Jung’s writings, including his letters, and on which his biographers disagree. Nevertheless, the film by David Cronenberg on the fraught relationship between the two — A Dangerous Method (2011) — similarly depicts Jung as a womaniser, specifically regarding Sabina Spielrein (who was one of his patients and eventually became one of the first female psychoanalysts).

Similarly, the character of the beautiful heiress who loses her memory after being viciously assaulted, Nora Acton, is based on the subject of one of Freud’s best-known cases, to wit, Dora (which was not her real name), complete with all the relationships in which she is inscribed in the book; even the Oedipal account of Nora’s hysteria, given to Younger by Freud in the book, is the very explanation of her condition Freud provided to the actual, historical Dora.

To sum up — this may be a novel, but it succeeds in conveying Freud’s revolutionary understanding of human beings, enhancing their import by situating them in the context of a series of (sometimes fictional, sometimes factual) human actions that bear out Freud’s deeply disturbing account of the unconscious motives of our actions.

If anything, the second of the two novels delves even deeper into the Freudian intellectual adventure — and at a time when its subject matter, the eponymous “death instinct” has again been on full, and disconcerting, display in the history of the world. After all, it manifested itself in the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington, DC, as well as in its aftermath; the subsequent US invasion of Afghanistan (which triggered a war with the Taliban that still rages today).

As well as referring to it in his Author’s Note, Rubenfeld pointedly foregrounds the connection with 9/11 by opening the narrative with the massive, historical Wall Street bombing on September 16 1920 , the perpetrators of which have not been identified to this day.

Of course, any Freud aficionado (like myself), would know that the death instinct (or “death drive”, or Thanatos), marks a turning point in Freud’s theorisation of the human psyche in relation to the unconscious. Further, that it is intimately connected with the Great War, or World War I, which ended in 1918 and furnished Freud with the evidence that his theory as formulated until then lacked a crucial theoretical component. Until then, he had sought (and apparently succeeded) to explain human action in terms of the workings of the “pleasure principle” — the unconscious mechanism that explained actions as directed at restoring a condition of “pleasure”, or rather, “the absence of unpleasure (pain)”.

Then, having witnessed what were known as “war neuroses” on the part of “shell-shocked” survivors of the war, as well as what appeared to be strange play-behaviour on the part of his young grandson, Freud was impelled to change his mind. What his grandson’s game and the behaviour of soldiers who experienced “shell shock” had in common, was the element of repetition — or what Freud labelled the “repetition-compulsion” (Wiederholungszwang in German) — and not just any repetition, but repeating something painful, such as the memory of seeing their comrades blown to bits next to them, or in his grandson’s case playing a “fort – da” (“away – back”) game with a cotton reel as reassurance that his mother (represented by the reel) would come back for him.

This clashed with the pleasure principle, because it exacerbated pain or unpleasure instead of removing it. Hence Freud posited the death instinct or drive, which he saw as being more fundamental than the pleasure principle, and manifested itself in two ways: aggression (towards others as well as towards oneself in bouts of self-destruction) and the conservative tendency to return to a (previous) state of comfort (one’s comfort zone).

Predictably, the action in the novel focuses mainly on the aggressive/destructive side of the death instinct, from the massive explosion at the US Treasury in Manhattan in September 1920 (where many people died), to a plot to trigger a war against Mexico to prevent it from nationalising American-owned oil wells, and perhaps most intriguingly, to a catatonic young French boy, Luc, who has not spoken for a long time — since his parents were killed by German soldiers near where he and his sister, Colette, were hiding.

The character from the first novel, Dr Stratham Younger, is also a central figure in The Death Instinct, where he meets Colette and her brother during the war, where he served as medical officer. Having fallen in love with Colette, who is not immediately accepted at the Sorbonne again after the war, he secures employment for her in America, where she endures a number of puzzling, successive attacks by strangers. She escapes largely unhurt because of the intervention of Younger and his friend, police captain Jimmy Littlemore.

There are two main narrative threads: Littlemore’s investigation of the explosion and concomitant disappearance of gold from the US Treasury, and Younger’s attempt to assist Colette in having her brother cured of his catatonia, which takes them to Vienna to see Freud. It turns out that Colette also wants to see a German soldier, ostensibly because she was engaged to him during the war, but things prove to be much more complicated than that … all I’ll say is that Freud uncovers a connection between Luc’s loss of speech and Colette’s determination to trace “her” German soldier.

This is not only a devilishly clever novel, but also — like its predecessor — a narrative adventure that functions to illuminate Freud’s psychoanalytic techniques and their far-reaching presuppositions concerning the human psyche for those familiar with his work as well as for newcomers to psychoanalysis.