For they have sown the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind: it hath no stalk: the bud shall yield no meal: if so be it yield, the strangers shall swallow it up. — Hosea 8:7

It felt strangely like a wake, watching the inevitability of Jacob Zuma’s election as the new head of the ANC, and proposing a wry toast. Unless he is convicted on corruption charges, which is far from certain, South Africa’s list-based proportional representation system makes him a near-certainty to become the next South African president in 2009.

That’s what you get for half-hearted commitment to market reforms and economic freedom.

Although many praise the ANC for having steered a sensible economic course, I’m far from enamoured with its record. Instead of freeing the economy, it has largely pursued a brand of national socialism not unlike that followed by the racist National Party during the apartheid years. That the intended beneficiaries of the government’s policy were infinitely more fair doesn’t change the fact that it tried — and failed — to deliver services that are beyond the ability of a government to deliver. If national socialism didn’t even work for a tiny fraction of South Africa’s population, what chance would it have of providing for the entire population?

Yes, inflation has been kept under control. Yes, economic growth has been positive. But South Africa has muddled along at a sluggish 3% or 4% GDP growth per annum, from a low base with high unemployment, in a global economy in which many developing economies achieved 8% or 10%. That’s what we needed to create the wealth to alleviate poverty and reduce unemployment. That’s not what we got.

Many industries were controlled by the government, and many reforms were bungled. Land redistribution has progressed (if that’s the right word) at a snail’s pace. The bureaucrats in charge of land affairs appear to be largely unaware of (or uninterested in) the basic business of agriculture. Despite a surfeit of willing sellers and willing mentors, land transfers were delayed for years while farms dilapidated and equipment rusted for lack of maintenance and capital investment. When they did happen, the transfer came with no regard to the seasons, so many changed hands at the most difficult time of the year for new farmers to begin operations.

Even then, the farms that did change hands were heavily encumbered: new farm owners couldn’t sell their land; they couldn’t even raise working capital because they couldn’t use their farms as collateral. Some emerging black farmers, perversely, face land-restitution claims themselves. In all the bureaucratic mess, full property rights were low on the agenda, even though they are the key to make investments, growth and economic success possible. The result? Highly visible failure, a rural economy in terminal decline, and many thousands of disgruntled poor people who have nowhere to turn.

When Aids emerged as a crisis, the government got itself in the most awful tizz, managing at various times to deny that HIV causes Aids, to refuse offers of free anti-Aids drugs from evil multinational profiteers, and to fail for years in rolling out antiretroviral treatment. Its intentions, immaterial though intentions are, were probably good. It merely tried to offer a holistic disease-management programme that included providing good nutrition, preventing opportunistic infections and building hospital capacity to manage out-patients who require regular long-term medication. Admirable. But ultimately, the determination for a large-scale government response proved useless, as South Africa’s Aids crisis grew to world-leading proportions.

When access to medicines became a populist issue, the government intervened by heavy-handed regulations imposed on pharmacies. It regulated not prices, but profits, and not profit margins, but absolute profit amounts per transaction in the form of fixed “dispensing fees”. As a result, a pharmacist that stocks slow-moving, high-value medication stands to gain no more than one that stocks fast-moving, inexpensive drugs. You can guess the results. Some drugs are simply no longer on the shelves, and pharmacists are going out of business hand over fist. The intention was to improve access to medical care, but the result left the people with less access than before the government intervened.

Private charity once thrived in South Africa, by offering tempting cash prizes in return for generous donations. Who can forget the ubiquitous scratch cards that funded charities such as Operation Hunger and the Ithuba Trust? What does the government do? Ban them, and establish a monopoly on anything even remotely resembling a lottery. This step severely hobbled a thriving and effective charity industry that was funding essential social investment and poverty relief, in favour of a profiteering national lottery. And even this, the government can’t manage. When it does operate, it struggles to distribute the proceeds that are meant to fund the government’s ambitious social development projects.

A similar thing happened with the casino industry. Once, a wide selection of mostly small venues offered good-value entertainment and created many jobs. Instead of regulating them to protect local communities, in the way licences impose conditions on liquor stores and bars, the government chose to establish a cosy cartel by issuing only a handful of high-value licences. Customers can now choose between loud, crass Vegas-style rip-off joints or loud, crass, Vegas-style rip-off joints.

Instead of making title deeds to township properties a priority, the government put a communist in charge of building matchbox houses for the poor. Some did indeed get built, but many promptly started falling apart. And as with farm redistribution, the “owners” of the new houses can’t sell them, or use them as collateral to raise money to start a business. So much for property rights. The government merely wasted public money on increasing, slightly, the stock of what Hernando de Soto famously called “dead capital”. Those people who did receive houses were left unhappy, and those who didn’t receive houses are now simply angry.

In telecommunications, the government established a monopoly, in partnership with profiteering foreign “equity partners”. The distressing results, ably summarised by William Currie and Robert Horwitz, read like the script of a disaster movie. Ironically, cellphones were considered expensive luxuries, inessential to “basic services”, and were left to a comparatively free private industry. Unlike “basic services”, which never were delivered despite 14 years of state-managed policy designed to do so, tens of millions of mobile handsets are now in the hands of South Africans, rich and poor. By some estimates, eight out of 10 households have access to telecommunications thanks to mobile telephony.

The government, disingenuously, tries to cover up its failures in telecoms by claiming credit for the fact that today, virtually everyone with a job has a cellphone. Meanwhile, not everyone has access to internet bandwidth, which, thanks to the monopoly on international cables, backbone networks and the local loop, is world-leading only in its ludicrous price and low quality. The government’s conflict of interest in both owning half the telecoms industry and tightly regulating it hasn’t helped. It talks of “market failure”, when a free market in telecoms never existed. It claims “privatisation” didn’t work, when all it did was turn a government department into a profiteering private monopoly, which is arguably the only worse option than a government-run telecoms system.

Throughout, the government neglected its most basic duties and core responsibilities, namely maintaining public order, protecting property rights and enforcing contract law. As a result, South Africa now faces a wave of crime that is highly organised and absurdly violent, and which thrives under either government impotence or, in some cases, active complicity at the highest levels.

I could cite many more examples, but in short, the Mbeki government ensured that its pretence at market-orientation was at best a half-hearted concession to foreign investors and what it saw as the white establishment whose wealth it needed. The result of its socialist instincts has been sluggish growth and nary a dent in unemployment. It ensured that neither the hobbled market nor the incompetent civil service managed to deliver the growth and prosperity that South Africans were promised as the dividend of freedom and a peaceful transition to democracy.

The sad thing is that undermining markets with ill-disguised socialist projects does not result in the realisation among the electorate that only economic liberty can generate the prosperity the country needs to deliver on its promises. Because the status quo had been described as “market-friendly”, the result is a rejection of those principles. Like those who argue that the failures of foreign aid to reduce poverty can be remedied simply by increasing foreign aid, or that failed government regulation can be fixed simply with more regulation, the people are demanding more from their government.

The communists, unionists and left-wing NGOs — Zuma’s support base — have been pushing collectivism and subsistence farming, in preference to sustainable agriculture that is able to feed the nation. They have argued for nationalising land and “essential” services. Despite the horrors socialism wrought in the rest of Africa, they want socialised healthcare, subsidised housing, state-created jobs and government service delivery. And who can blame them? They were promised services, and they didn’t get them. They were promised jobs that never materialised. They were promised prosperity, as if a government can wave a wand and conjure it up.

Jacob Zuma, and the new crop of unionists and Marxists that from today head up the ruling party, have promised to do the people’s bidding. Zuma has no apparent policies of his own. He has promised to bow to his left-wing support base, yet he has promised not to do anything to scare investors. He has promised to deal with Aids, though he apparently believes a vigorous after-action shower is an effective prophylactic against the disease. He has promised to curb crime, though he faces charges that prove him to be either corrupt or incredibly careless and naive. He promises to be all things to all people, and if anyone doubts it, just listen to all his people singing: “Bring me my machine gun!”

Having heard nothing but empty rhetoric, the people apparently stand ready to believe that a president Jacob Zuma can deliver where President Thabo Mbeki failed. That all will be well because “Zuma cares about the people”.

Just yesterday, someone asked me whether I think being populist or socialist really is worse than being corrupt, self-serving and possibly a rapist. Assuming for the sake of argument that those charges against Zuma are true, I answered that yes, a socialist rapes and pillages the entire country.

That’s the price of the ANC’s policy, which adopted the apartheid government’s national socialism instead of turning away from it. Having failed to liberate the economy, a Zuma-led South Africa will try to harness it in service to the people. It will merely extend the crony capitalism that has deeply corrupted this country, rather than freeing the people from patronage. It will create a new socialist elite, instead of permitting the kind of growth that creates jobs and clothes the poor. And the people will be too busy singing and dancing and celebrating the great victory of their populist idol to fret about the fact that enslaving the productive in service to the unproductive destroys the engine of the economy. Redistribution not only reduces the creation of new wealth, it also actively destroys productive capital.

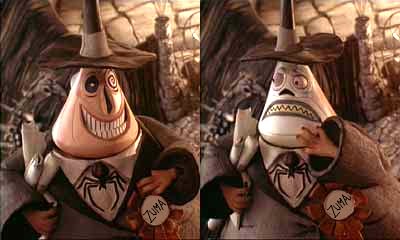

My gut feel about Zuma, my fear about the combination of populism and economic illiteracy that begets socialism, may be wrong. He did, after all, position himself as all things to all people, and the new unionist secretary general of the ANC promised its policy would not change. There are definitely two faces to Zuma. But I fear that his left-wing supporters will get to party in the short term, and as sure as night follows day, will face a devastating economic hangover.

They have sown the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind.

(First published on my own blog.)