I would like us to think together about two seemingly opposing observations made by Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko. In particular, about what these observations mean for black people in South Africa. Fanon and Biko were revolutionary humanists and, of course, Biko read and was influenced by Fanon.

In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon writes: “The inferiority complex [of black people] can be ascribed to a double process: first economic. Then, internalisation or rather the epidermalisation of this inferiority” (2008).

This black inferiority complex wears a multitude of masks: economic, political, cultural, social, psychological, emotional, spiritual. Its skin is twofold — the alienation and erasure of black humanity. In his study of black life, Fanon is a committed existential physician: “The analysis we are undertaking is psychological. It remains, nevertheless, evident that for us the true disalienation of … black [people] implies a brutal awareness of the social and economic realities” (2008).

Fanon is arguing that of the various deprivations suffered and endured by black people, economic lack or the “materiality of existence” is crucial among them. As if he feared he would be misunderstood — and he was not wrong — he further writes, “There’s no point sidling up crabwise with a mea culpa look, insisting it’s a matter of salvation of the soul” (2008).

Fanon is not naïvely advocating that economic resources and infrastructure are the only things black people need to restore their humanity. Rather, Fanon wants us to understand that the economics of colonial modernity and their current articulations have deprived black people of almost everything. Consequently, and to emphasise how salient economic provisioning is for rebuilding black lives, Fanon argues that “genuine disalienation will have been achieved only when things, in the most materialist sense, have resumed their rightful place” (1986).

For those who are in the habit of making misguided quantum leaps, it must be explicitly said that Fanon is not prescribing the worship of materialism as an antidote for the decay and death of black humanity. Neither is Fanon offering consumerism or so-called “retail therapy” as a capitalist fantasy and escape from the horrific histories and realities of black existence. Retail therapy is precisely what George W Bush prescribed for the American people soon after the 9/11 tragedy. “Go shopping more”, Bush told the Americans. It is anyone’s guess how that wisdom has been therapeutic for American society.

Fanon is not saying to hell with “the souls of black folk” (Du Bois, 1903). Rather, he is saying we should guard against the tendency to oversimplify and relegate the question of black liberation to spiritual salvation, folklore, traditional song and dance, and an entertaining Hollywood daydream about a Wakanda.

Rather, Fanon is saying that if we are serious – and we should be – about black freedom then we should deal foremost with the economic and social realities of black liberation. In other words, as black people we should be wholly dissatisfied with merely surviving the white supremacy-racism agenda that continues to annihilate black beauty and excellence. Black souls should insist on flourishing like the melanin gods of empires and kingdoms of old buried in our bones. For such a glorious goal, Fanon is insisting that the economic wealth of black peoples must be restored to its rightful place – their hands.

In I Write What I Like, Biko takes a different route. He writes, “Material want is bad enough, but coupled with spiritual poverty it kills. And this latter is probably the one that creates mountains of obstacles in the normal course of emancipation of the black people” (1978).

Like Fanon, Biko is preoccupied with the kind of human being that white supremacy-racism creates out of black people. For Biko, white supremacy-racism produces a human figure that is paradoxically an absence of the human – “All in all the black [hu]man has become a shell, a shadow… [hu]man, completely defeated, drowning in [its] own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.” Black humanity is in bondage.

Fanon and Biko come into conversation and Biko wants to take Fanon further.

Biko concedes Fanon’s argument that black people as a group are economically oppressed and that this is the cause of great lack and desire. Fanon wants this socioeconomic lack and desire to be prioritised. Biko, like Fanon, is a black existential physician and he offers a further diagnosis of black life – spiritual poverty.

Biko is saying at least two things here. On the one hand, it is that white supremacy-racism has covetously consumed black humanity to the point of spiritual bankruptcy. If you are in doubt, you need only observe the extent to which black people are fully co-opted into keeping white supremacy alive.

On the other hand, and because of the above, Biko is warning us that economic liberation alone will not restore black humanity. We must also prioritise the investment of economic resources to waging psychological warfare against the perversion and poverty of black consciousness. Black souls, minds and hearts must be purged of the delusions, illusions and pathologies of white supremacy-racism.

Here Biko pushes back on Fanon – it is indeed a matter of the salvation of black souls. I think Fanon would concede as much. The work before us therefore, is the economics and consciousness of black freedom and the invention of a humane world in which to live and die.

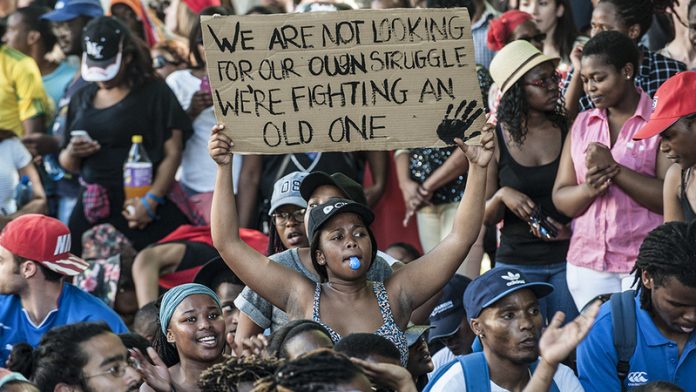

Twenty-six years later we should be disabused of the illusion that democracy means black freedom. Casting votes may be as good as tossing a coin into a wishing well.

We now know that black politicians are committed to self-enrichment through corruption by all means and at all costs. Even the current Covid-19 pandemic could not half-awaken politicians’ empathy and conscience for millions of black souls in need. Wherever and whenever money is available, our black politicians are like vultures let loose on a fresh corpse. Our politicians are addicted to money and materialism, and like any addictive drug, they must have it even at the risk of destroying their own lives.

Colonial modernity was driven by the same insatiable addiction. The cult of materialism and spiritual bankruptcy between oppressive and democratic regimes should be clear to us now. Quite frankly then, we cannot look to politicians for anything that vaguely resembles an economics of black freedom and a spiritual enriching of black souls. Ordinary black people are their own best chance at a dignified life in post-apartheid South Africa.

What an economics and consciousness of black freedom might look like

If black people are to have a chance at building economic wealth, this will in all likelihood happen over a long period of time, probably generations, given how economically handicapped we are as a group. However, we will not get there by prayers, reparations, tenders and social grants.

Instead, we must undertake crucial work as a group to clear psychological hurdles and emotional additions to materialism and consumerism. We must decisively change our attitude about money and how we spend the little financial resources we have as individuals and families. Black people are not the only group that spends money (and tragically, credit) on trivialities, conveniences, addictions and luxury goods. The difference is that as black people we simply cannot afford to be doing this at the scale at which we currently are because we are last in the economic race.

It is for this reason that black people must be committed to a future of economic success than to immediate gratification, “flexing” and other financially immature decisions and behaviours. The global culture of consumerism and material worship does not do any favours for our future financial success – we save nothing in the present and invest nothing for the future. Or, as Big K.R.I.T puts it:

“Mama, I made it, got my chain now

I got that Benz too

I got my Louis Vuitton and my Gucci shoes…

But I’m scared it all ain’t enough to free my soul

Lord, Mama, I made it.”

We ought to make a commitment to buying far less expensive consumer goods and make a habit of thrifting and buying good second-hand cars. It will also add to our glorious goal to cut back on phuza Thursdays, ratchet Fridays, shisa nyama Saturdays, and car wash Sundays. All this instant gratification drains financial resources we could be saving and investing for our futures.

But then again, we first have to believe that we have a future. We first have to believe that our lives are meaningful and have value and that have beauty to offer the world.

This is why we cannot separate our economic prosperity from an enlivened and proud black consciousness. Money can buy us convenience and luxury but not freedom. Black freedom will be paid for by the individual and collective renewing of our minds and hearts. As a group, we must (re)learn how to respect, carry with dignity and love ourselves before we demand it from anyone else.

No group will give this original spark of freedom to us. This divine love is encoded in our melanin – it is the freedom to see ourselves for who and what we really are and not through the fog of white supremacy-racism and the distorted eyes and hearts of centuries of oppression. We must realise that capitalism, materialism and consumerism are continuations of oppression and that black people, because of our histories of oppression, are the worst losers in this game of plastic thrones and social media kings and “slay” queens.

This is a sort of global nightmare and in it black people are caught in a sleep paralysis.

As a group, we will not see a day of economic and psychological freedom (no matter how wealthy we may be as individuals) until we purge ourselves of the demon of self-hatred.

Black people, in many instances, do not like each other as a group – mistrust, jealousy, suspicion, anger, hatred and mean-spiritedness are currencies we trade daily among ourselves. For a moment, we may take a break from kicking each other’s teeth in while #BlackLivesMatter is trending or some other racially charged issue is unfolding. If we can’t cooperate as a group, how are we to live black freedom, love, beauty and excellence? Perhaps we should remind ourselves that freedom is none of the fantasies sold to us by the media.

Freedom is more simple and noble, yet more difficult to attain. Freedom is a personal, familial and group way of being and becoming in the world. If you like, freedom is a way of living in the world that capitalism can never commodify and commercialise. So Fanon is correct to emphasise the importance of black economic prosperity to the extent that dignified ways of being and becoming require strategic planning and use of economic resources, infrastructure and networks. This is the work we are doing too little of.

Equally if not slightly more important than “40 acres and a mule”, to use an American example, is unyoking ourselves from the bondage of consciousness that lynches millions of black souls in the great tree of life. “All of the great empires of the future will be empires of the mind”, said Winston Churchill. From this great capitalist empire of mindless materialism and consumerism we as black people must distance ourselves. We must forge a new and different consciousness that will build a humane, self-loving and self-respecting future for ourselves and for the flesh of our flesh.