It sucks being an over-educated Joburg northern suburbs white liberal of a certain age. It really does. You haven’t given over to the cynicism of your parents’ generation, so you’re perpetually in knots over the twin anxieties of your whiteness and your privilege. You spent years at university studying critical discourse analysis, so you never get to enjoy the gloriously unreflective anger of the Steve Hofmeyr or the Julius crowd. Conservatives and leftists appal you in equal measure, not so much by their opinions, but in their bewildering conviction of their own rightness.

(What does it feel like? To be utterly convinced you are right, no matter what, all the time?)

You’re always in the middle, so aware of everyone else’s competing views that it’s impossible to have one of your own. Even as you’re incubating an opinion, you’re developing an analysis of it, so you end up so aware of why you feel the way you do, and how compromised you are by your own history and upbringing, that it’s pointless saying it in the first place. It’s a sort of ideological autism, where nothing can be filtered. So you’re perpetually on the brink of an existential meltdown, painfully aware as you are of your own irrelevance.

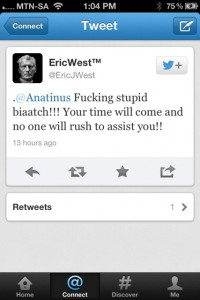

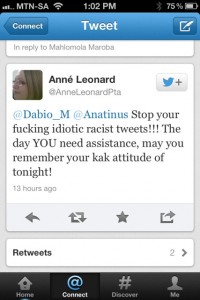

When you tweet about how much it sucks to be a northern suburbs white liberal, you get accused of being a racist by the very people who hate your type so much they include it in their Twitter bios:

Here’s how I ended up being called a “stupid biaatch”. It was late on Sunday night. I was scrolling through Twitter, reflecting on the magnitude of the St Francis fire. A heated argument was developing on Twitter between those who were horrified by the sight of all those homes going up in flames, and those who compared the response to this disaster with the response to shack fires.

I started tweeting a response to express solidarity with the property owners of St Francis and then I stopped myself. This is how my thought process then evolved, roughly speaking (I’ve had three hours’ sleep; if I’m less than lucid, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it).

Thought 1: I can’t tweet about St Francis. Too glib, too pointless (my tweet won’t help put out the fires).

Thought 2: By tweeting about St Francis, I’m just underlining the point being made by others, that people in my position care a whole lot more about people like me than they do about people who happen to be poor and, for the most part, black.

Thought 3: Maybe I should tweet about shack fires. No, wait, that would make me a hypocrite because I’d be doing it for show.

Thought 4: Actually, why the hell shouldn’t I tweet about St Francis? I’d be distraught if one of those houses belonged to my family (we once had a holiday home burn down, so we know what it’s like). Why does caring about anything in South Africa always have to be rendered politically correct by including a disclaimer acknowledging the poor?

Thought 5: But it’s true. Disasters featuring rich people and nice things attract far more attention than disasters that affect the poor. (This is true of news across the world.)

Thought 6: But

Thought 7: And on the other hand

Thought 8: Oh bugger it.

Thought 9: Let me tweet about my screwed up, guilt-ridden and excessively self-aware thought process in 140 characters.

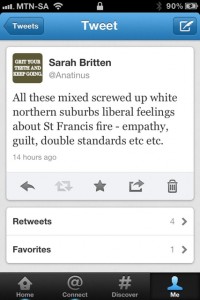

So I tweeted, eliminating the personal pronoun and overt references to myself as I normally do to save on characters:

(On second viewing, I can understand why that might get misinterpreted — my fault for forgetting that not everyone on Twitter has comprehension skills. To the charming people who let me know exactly what they thought of me, let me be absolutely clear: I was actually referring to myself.)

Oh, the joy of pissing off the Woolworths boycott crowd. Ironic self-reflection on one’s own compromised and conflicted worldview is evidently verboten; self-awareness and ambiguity don’t sit well with the news24 comment crowd, who now play the race card with as much alacrity as the politicians they love to hate. Clearly, self-criticism is now officially deemed unacceptable by the professionally offended, who spend their lives looking for reasons to feel aggrieved regardless of the actual content of a piece of communication, whether it’s an ad, a tweet or the wording in a recruitment policy.

What do you do? Sigh? Shrug? In my case, you write, knowing that none of this will change opinions that were set in stone in the Triassic — but you do it anyway. And yes, next time I’ll make it absolutely clear when I’m tweeting about myself.