Many in the venerable older generation that ensured the demise of apartheid are departing. They have played their part. No one lives forever. It is rare to find someone that is all good or someone that is all bad. Humans have strengths and shortcomings. Humans evolve overtime. Context and circumstances can change views and perspectives. Many an extraordinary person is an accident of their times and context.

In one of Mitch Albom’s extraordinary novels, The Five People You Meet in Heaven, Eddie (the old man who dies in an accident while trying to save a life) meets someone (the first person he meets in heaven) and that person tells Eddie that “people often belittle the place where they are born. But heaven can be found in the most unlikely corners. And heaven itself has many steps.” Albom’s masterpiece novel, very much like his memoir Tuesdays With Morrie, has many important life lessons. We have to do our best to live well or to live a life of meaning and purpose.

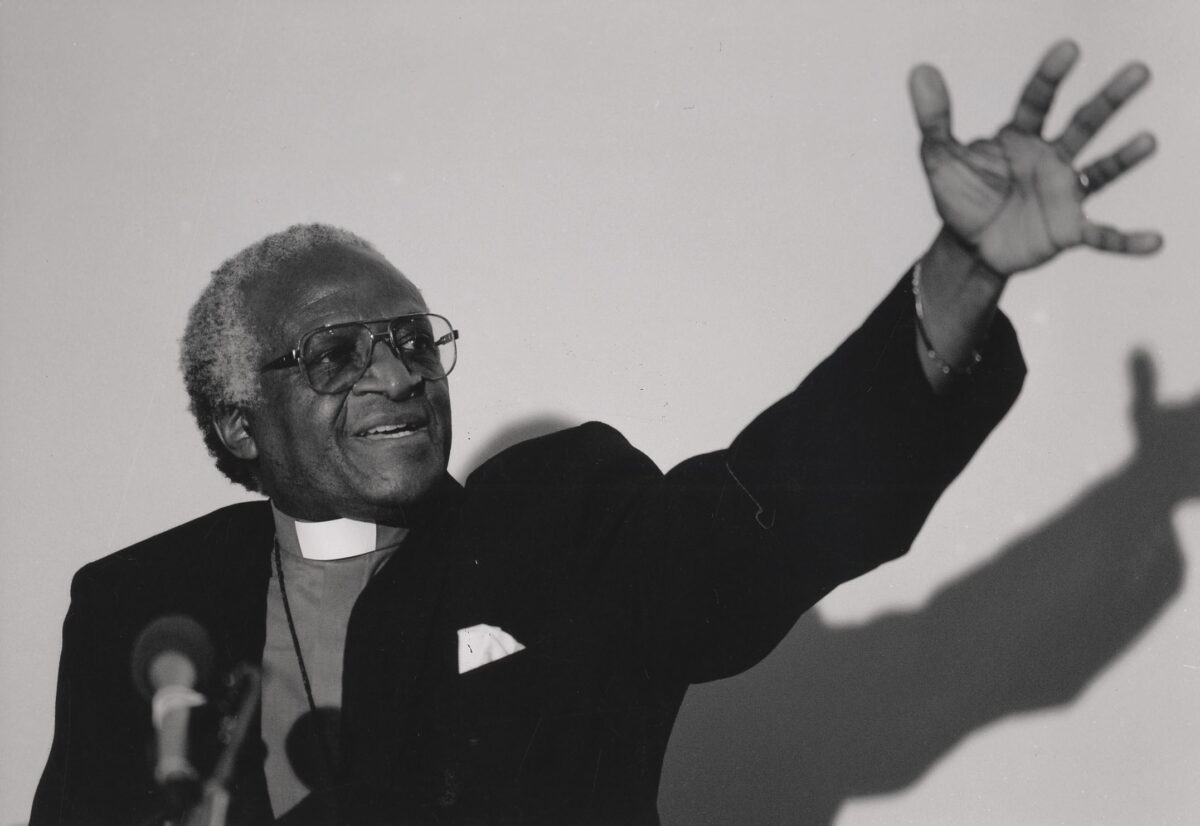

Among other things, the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu brought back the debate about the role of his generation in the context of the challenges that South Africa continues to face, almost 30 years since the dawn of democracy. It is undebatable that Tutu and those of his generation lived a life of meaning and purpose. They never belittled where they were born.

The fundamental question of what more they could have done in the making of a better country should not be dismissed. South Africa has been drifting further away from the society that was envisaged by the liberation programme. The majority of South Africans continue to face many hardships, inequalities have remained high and racism continues unabated.

The rainbow nation that Tutu envisioned has become a pipedream. South Africans are unable to coalesce, co-exist and build a common future. Given South Africa’s ugly history and the repulsive colonial-apartheid system, the common future must involve the sharing of resources and an appropriate balance of power and influence among all racial groups. Could Tutu and his generation have done more to ensure this; at least to try to make the rainbow nation a possibility?

The aspiration of a rainbow nation is dissipating largely because nation building has failed. One of the leading thinkers on nation building, Benedict Anderson, views a nation as “an imagined political community — and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign … the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship.” We surely could have done better in the pursuit of social cohesion.

As we bid farewell to the older generation that brought us political freedoms, we must never forget where we come from as a society and we dare not belittle the place we were born. We should equally, if not more, be inspired to forgive. Forgiving is not the same as forgetting.

Memory can play many roles; good and bad. In her book capturing her interviews with an apartheid assassin, Eugene de Kock, Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela advances a view that if memory is kept alive to cultivate old hatred and resentments, it is likely to culminate in vengeance and repetition of violence, but if memory is kept alive to transcend hateful emotions, then remembering can be healing. It is a complex issue.

It is indeed critical that memory in the context of South Africa can be used to advance nation building. Memory, also in terms of heritage, can be an instrument for healing and bringing about the rainbow nation that Tutu hoped for. It is never too late or better late than never. As Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela puts it, “when perpetrators express remorse … they are revalidating the victim’s pain — in a sense giving his or her humanity back”.

I, however, think that forgiveness is a solitary journey. Each individual weighs up many factors in deciding whether to forgive or not. This is not to downplay the value of forgiveness. As individuals, there may be instances where we first have to forgive ourselves before we can forgive those we consider to have harmed us.

Functionally, memory inspires hopes and aspirations for the future. Memory helps victims tell their stories. Through memory, victims share their dignities, sorrows, disappointments and expectations with others. As they recall their experiences, they hear one another and extend invitations to others to “witness” their lives. They learn about issues of concern and possible ways of addressing those concerns.

Sadly, the majority of South Africans no longer regard democratic South Africa as a beacon of hope, because it would seem that the economic interests of former oppressors and beneficiaries of the apartheid regime have been expanded and protected. As academic Tshepo Lephakga points out, “the negotiated settlement resulted, in line with the colonial project, in the conquerors receiving their first prize, namely economic power, while the conquered received their first prize, namely political power under constitutional democracy”. Joel Modiri contends that “the failure to redress the structural continuity of colonial-apartheid renders the Constitution’s extension of universal suffrage, citizenship and human rights to black people hollow and abstract.”

As we celebrate the lives and legacies of those who ensured that apartheid collapsed, we should use the opportunity to revisit the memory that brought us here. We should continue to strive to turn that memory into a weapon for lasting positive change. That also requires that we remember to forgive.