“The situation in our townships is so disgusting that you sometimes ask yourself a question which has got no answer and that is, ‘Why did God create a human being?’ We are always running away from the SADF troops … these army troops pretend to be our friends while on the other hand they are killing us like dogs. They play football with us in order to get us unaware.” Bathandwa (15)

“Life nowadays is like a sick butterfly. To many of us it is not worth living when it is like this. The little kids don’t understand why they have been put in jail.” Bothale (12)

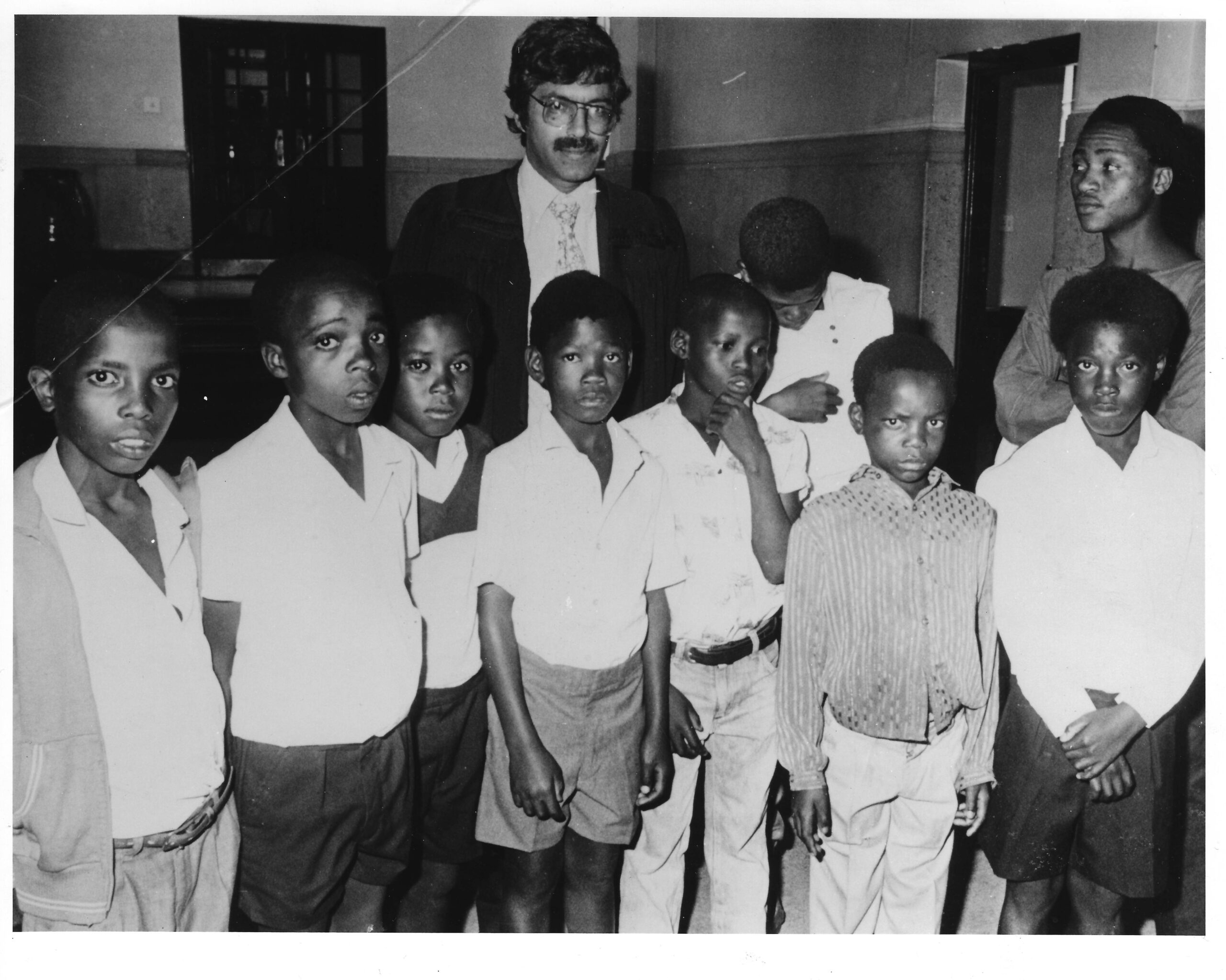

ANC stalwart Ruth Mompati quoted a student at the 1987 Children, Repression and the Law in South Africa Conference: “We have no way of defending ourselves against the police guns which attack us in the schools, and that is why we have left our country to come and train … There are no children in South Africa.”

Black children had never been treated “like children” in South Africa. By the time they became politically involved many were already contributing to the household income. From the age of eight, more than 60 000 children were employed as farm labourers, some earning as little as $1 a day. Others worked for white shopkeepers or performed unpaid labour within their communities, taking care of the ill or the elderly. As a child, activist Elias Kodisang worked as a golf caddy.

“From that early stage it was clear to us that we needed to find ways of educating ourselves. We started looking around ourselves. I enjoyed biology, so I would teach biology. So we then formed our own classes and taught ourselves. Occasionally a badly photocopied paper and an underground book would appear and it would be passed on to people we trust. A lot of Steve Biko’s writings were passed in this way,” Kodisang remembers.

Building on the lessons of 1976, they organised so that momentum would not be lost after a wave of arrests. “Every township started forming its own youth congress. There would be links between all of the different movements and support for campaigns that were happening particularly whenever there was a strike by workers, it was the youth that could take it on themselves.”

Far away in Wynberg, Cape Town, Ashley Forbes learned the same thing. Prolific grassroots organising was taking place everywhere, very often aware of but not connected to what was happening elsewhere. The fear of spies and agent provocateurs was too great. The underground cells Ashley and his comrades organised across the Cape Flats was done entirely without contact with the ANC, which they only joined after Ashley fled the country, and went on a cross country search across southern Africa for them.

As part of this movement, youth congresses sought alternative institutions of governance. Where authorities withdraw services, the youth played a role in rubbish removal: “People took over abandoned lots and dumps and turned them into parks. There was a movement around self-education, there was a cultural movement and a debate movement. There were underground reading clubs that passed novels around.”

Youths built popular forms of local organisation and governance and in so doing brought about the collapse of black local authorities, informer networks and the expulsion of collaborators such as police officers from the townships. This culture of organising meant that from a very young age, as young as five years old, children were taught what it means to organise and to hold a community meeting, and the processes of debate and decision making. “We grew up with traditions of grassroots democracy and the culture of being democratic and consultative.”

Young people leveraged the power they had as a result of their fearlessness before the police, to impose their own form of street policing. “There was a very violent current underneath that felt the system is violent, we have no choice but to respond in a similar way.”

As a result, Elias remembers, “there was no crime, not a single crime in the township. As a woman you could move through the township from one end to another through abandoned areas at 1AM and not a single person would touch you because it was understood that criminality was not to be allowed. “

The punishment of offenders involved humiliation. When a crime took place a court would be opened immediately, the community would be called, the court would declare what the accused was accused of and punishment was immediate. “No one was killed but they would be beaten severely with sjambok and a cane. They would be warned that next time it happens, it would be necklacing for you.”

Harsh as it may sound, it is significant that community justice and control was “tempered towards reconciliation rather than retribution” – as Frank Chikane emphasised at the Harare Conference – significant because these same young people were in this period, being terrorised by a viciously punitive criminal justice system. After the end of apartheid, under the guise of unity, thousands of independent women’s, youth and community movements were subsumed into the ANC Youth League and the ANC Women’s League.

At the same time, Elias Kodisang explains, state-sponsored violence was unleashed in townships through the sponsoring of askaris and training of the Inkatha Freedom Party. This same generation that came to shape the trade union movements became the first wave targeted for retrenchments in favour of young workers.

“You find an entire generation thrown out of anything and everything. They no longer have democratic institutions that can hold them, or the income that comes from working and they are subject to extreme forms of violence. That was all part of the total war, which was waged in collaboration with sections of the movement,” explains Kodisang.

Today, movements like Fees must Fall must rebuild the culture and relearn the lessons that were lost through demobilisation, he reflects. “It’s one of the great tragedies in SA,” says Kodisang. “The positive cultures of intolerance against women abuse, alternative working class systems of education, parks and understanding of life as a working class person, that strong working class identity was lost – so the new generation must find their own path.”

While the Harare Conference emphasised the suffering and trauma of South African children, it is important to remember that the children and young people themselves emphasised their agency. It is an agency that tells the story of one of the twentieth century’s most important youth-led grassroots democracy movements.

This article was developed as part of the blog project “Troubling Power: Stories and ideas for a more just and open southern Africa”, which marks the 40th anniversary of the Canon Collins Educational and Legal Assistance Trust.

Elias Kodisang, who cooperated in the writing of this piece, is a Canon Collins Scholar.