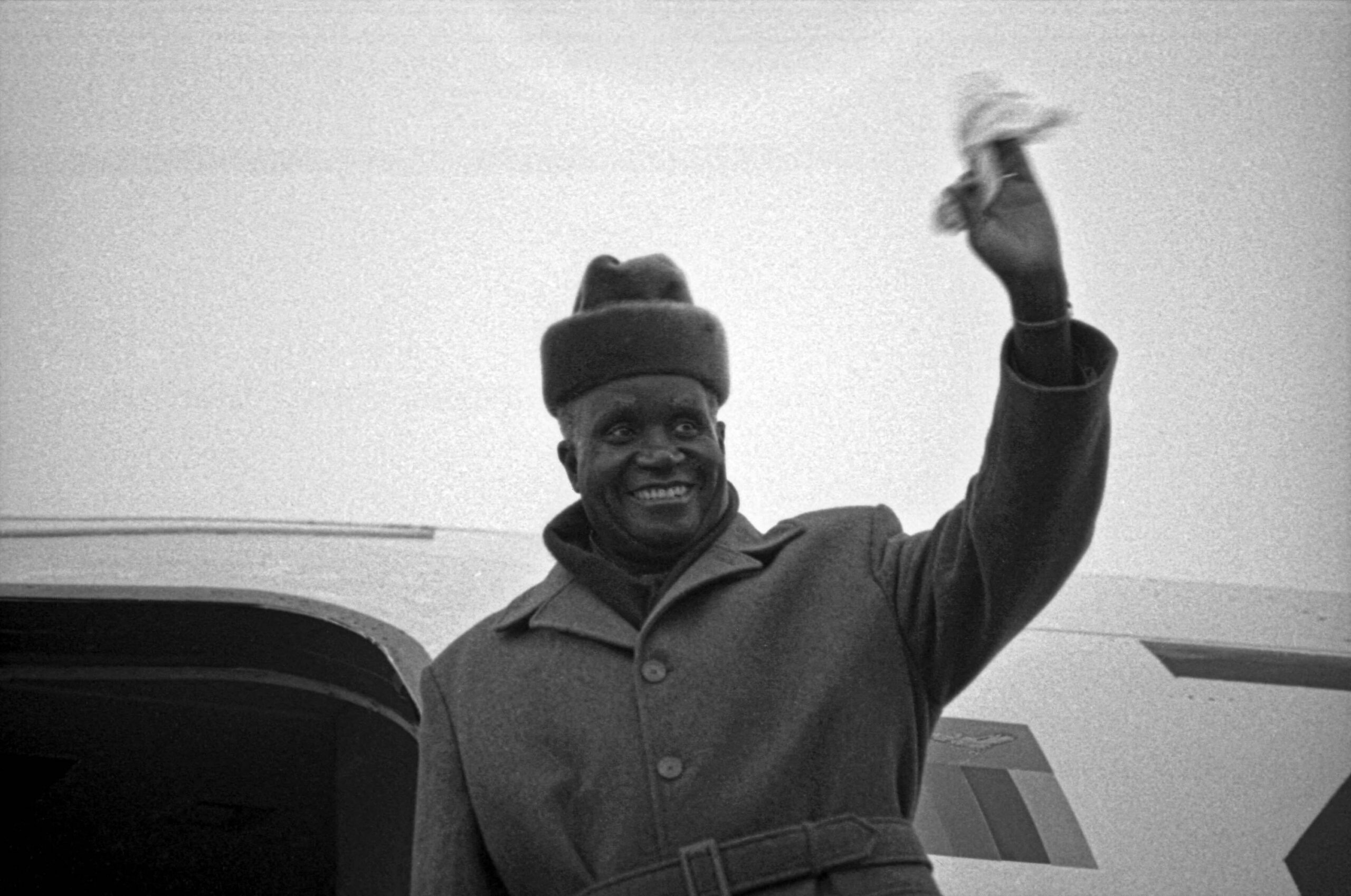

The former President of Zambia, Kenneth David Buchizya Kaunda, was the last of the 1960s philosopher leaders who fought for African liberation. As we celebrate his life and legacy it is important that we learn from his stance on pacifism and violence.

In his almost forgotten book, Kaunda on Violence, he presents his philosophy of pacifism, which is characterised by African humanism. His is not an idealist but a realist view of the dilemmas facing pacifist leaders in a violent world. Kaunda was an idealist.

He advocated an idealism that seeks the highest values and not merely those that are the best fit for the times. In pursuit of this, he came to believe in the need to fight for what is good, even if this meant making deliberate and careful decisions to shed blood. The alternative, he came to think, could often lead to much worse outcomes.

Kaunda realised that political leadership involves taking the heavy responsibility of using violence because good governance cannot be achieved while recklessly and permanently putting away the powerful weapons of violence. Kaunda’s ubuntu led him to embrace the violence of liberation struggles in states that neighbour Zambia.

Kaunda played a leading role in ending colonial rule and apartheid in Southern Africa. As many commentators have said since news of his death on 17 June, he ensured that the country hosted liberation movements from neighbouring countries.

But he also made violent mistakes. Writing in response to news that, on 29 January last year, Kaunda was nominated for a Nobel peace prize, a Zambian citizen commented that although Kaunda deserved the award for his contributions to the fight against apartheid, we must also acknowledge the violence and repression that marred his Zambian postcolonial country. There is a painful connection between Kaunda’s one-party state politics and how his domestic politics failed to embody non-violence.

For people who are interested in the prospect of a continent free of political violence, there is much to learn from studying the life, times and intellectual heritage of Kaunda.

African cultures and philosophies are given forms and meanings in the lives and experiences of Africans, including in their political strivings. Kaunda speaks of Zambian humanism as a tree whose roots determine its growth above the surface. Zambian humanism is rooted in deep precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial experiences. The Zambian humanism of Kaunda is of a piece with Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa. It is also foundational to the African thought system that Stanlake Samkange and his wife Tommie Anderson Samkange named hunhu or ubuntu in their 1980 classic, Hunhuism or Ubuntuism.

Kaunda’s experiences were marked by change. He lived through a time when Zambian colonial and postcolonial identity itself was being formed, bringing together diverse indigenous and colonial immigrant populations.

In the period 1888 to 1910, through a series of concessions signed with local chiefs, the territory that is now known as Zambia came under the influence of the British South Africa Company. In 1923 the British government allowed the power of the British South African Company to expire in the area. The British government then annexed Zambia. So it was only in 1924 that Zambia became a protectorate under the British Colonial Office.

Kaunda was born in 1924 and rose to champion an idea of culture and humanism that is rooted in African traditional thought intermeshed with socialist, Christian, and Gandhian thought — Kaunda has sometimes been labelled the African Gandhi.

Kaunda has to be read not just contextually, but also holistically. Doing that can reveal, for example, how Christianity — which is complexly intertwined with colonialism — influenced his thoughts. To extend Kaunda’s tree analogy, one can say that humanism in colonial and postcolonial Zambia was watered with Christian beliefs. This watering manifests itself in the way the outer growth-rings have formed. But the roots remain those of ubuntu. Reading Kaunda in this way teaches that the branches of ubuntu, which one finds across Africa, are exposed to different climatic conditions, but the roots remain the same.

We need to be careful, because the root metaphor can easily project the false impression that there is an inescapable essence to culture, in particular that the African moral philosophy of ubuntu has a predetermined “genetic” code when cultures and their meanings are composed of fluid, negotiated, blended, meshed and contested acts.It is important to understand how African moral philosophy informs peace and violence. A good start is Kaunda on Violence. For it is invaluable that, on the matter of war and peace, Kaunda has left a political legacy that is accompanied by a philosophical heritage.