Two months ago I decided to learn to speak isiXhosa. This is a big thing for a 53-year-old — some might say impossible. Others might say it is unnecessary. They might be right in strictly practical terms. I don’t need to speak isiXhosa. Very, very seldom do I have to communicate with someone who speaks neither English nor Afrikaans, and when that person happens to be a South African, there are usually others close at hand who will interpret for us both. Even in my job as a doctor it has never really been essential. As a result many people on hearing this have asked me why I bother?

Here’s why.

Rhodes is partly to blame. The events of this past year have made me aware for the first time of the depth of black anger at white economic domination and the attitude of white supremacy that I didn’t think or know I had. For all the messiness of the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement and its fall out, it has achieved one objective, that of opening the eyes of a white male who enjoyed the benefits of a system (irrespective of whether I supported it or not), and who might have thought that the first democratic elections in 1994 and the 21 years hence fixed everything. Clearly I was wrong.

The only thing I can think of doing in response to this new awareness that is likely to make any substantive difference to every black person I happen to meet is to try to converse in his/her first language, rather than expect that we communicate in mine. Of course I cannot learn all our indigenous languages, but starting with the one I am most likely to use makes good sense. This move towards reconciliation is mine to make, and no one else’s. More importantly, it expects or demands nothing of anyone else, and everything from me.

Mmusi Maimane’s recent rise to leadership of the DA (I called it several weeks beforehand here) is again a sign that South Africa’s future lies in a shared prosperity, where black and white are equals and could be both neighbours and friends. That depends on equality in all things to do with human value, and knowing each other’s languages is a big step towards that goal. Maimane has inspired me to be proactive about positive change in South Africa, and that will more than likely mean getting more involved via local politics in my own community, over 50% of whom are isiXhosa speaking.

I lost my Dad about 18 months ago. One of the many things I admired about him was his fluency in Swahili, consequent to his childhood on a Kenyan coffee farm. This ability in a sense “Africanised” him beyond the place of his birth, nationality, the colour of his skin and his political beliefs. I realise now that I can emulate him in this by learning an African language for myself. Perhaps, I ask myself, this might be an effort, in this tumultuous time where “whiteness” is seen as an oppressive force, towards cementing my entitlement in all my whiteness to be here? I admit freely that this sounds pretty insecure, but insecurity abounds in our current political discourse, and I would not be surprised if many whites live with an increasing sense thereof. Put it this way: the governing party has done absolutely nothing to alleviate white insecurity, and the EFF goes out of its way to increase it.

So, best intentions and good reasons aside, what benefits has this experience of mine brought so far?

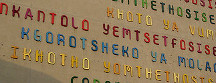

Firstly, I have gained an insight into a remarkable culture. isiXhosa as a language combines poetry, idiom and logic in a manner that has deepened my respect for a people about whom I knew very little. Ignorance is a big barrier to interracial harmony. White South Africans know too little about the cultures of the vast majority of our population, and this clearly needs to change.

Secondly, my fumbling attempts to initiate and maintain conversation with isiXhosa folk are welcomed with universal approval. All it takes are a few words to build a bridge that would not otherwise have been there. I am often asked whether I grew up in the Eastern Cape? No. I am learning from scratch now, today, the “hard” way. Every Xhosa stranger I interact with in this manner has been pleased at finding out that I think his/her culture and language are worth knowing and understanding. It is truly amazing what a difference just a few words can make …

Thirdly, it has been easier and more fun than I thought it would be. I have subscribed to an excellent course by the name of SpeakEasyXhosa. This is available online with video lectures, handouts, and tests with immediately marked results. The system is very affordable, methodical and highly practical. Other excellent resources are the flashcard apps on the Apple IOS and Android systems — Chegg, and Quizlet. Flashcards are an effective way to learn vocabulary over a long term, and both have extensive databases made by other students of isiXhosa ready for immediate download that one can use.

Nelson Mandela said it well when he made the observation that speaking a common language to another person speaks to that person’s head, whereas speaking in that person’s own language to him speaks to his heart. I can see that is indeed true, and perhaps it goes deeper than this, that both hearts change. I can sense in myself a metamorphosis, perhaps to becoming a South African citizen no longer defined or classified by racial stereotypes, and able to change our country for the better. It’s a tough ask, but a critical one.

The final words go to my wife, who shook her head and muttered two months ago that this was just a passing phase.

“Ndiyakuthanda kakhulu, Sweetie, kodwa uza kubona ukuba urongo:)”