Writing a standard book review risks creating a vapid commercial about the new publication. This is different to the journey that serious reading is, and journaling about that reading. Reading frequently, and returning to books that move you, creates a “spiritual travelogue”, and begins to resemble a series of religious stations, reference points to look back at on the road travelled.

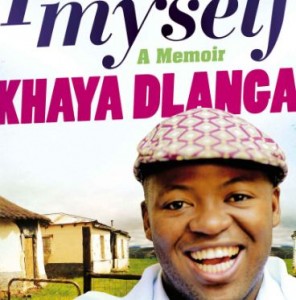

A well-written and well-edited memoir, as it is often personal, will also have a lot to say about the reader’s written response (To Quote Myself is a wonderful book, necessary reading for all South Africans, and should be in the SA high school syllabus). So what intrigues me is the following sub-genre. A specific kind of response to a good book that reflects – even to the level of confession – what is going on in the critic’s mind and heart as he critiques. A sub-genre that lays out in the open the set of assumptions and standards the critic brings to bear, even his own autobiography, as he evaluates the book in front of him. That, I realised, was the only way I could honestly approach Khaya’s memoir.

Further, there are two kinds of memoir-reading experiences for me. Firstly, there are the histories about countries or areas in a country I have never been to or which is set in a different era. Secondly, and Khaya’s memoir broadly falls into this category, there are the ones about countries I have lived in, such as South Africa, the home of my birth and where I lived till the age of 41 . Then there is China, where I worked for seven years. Thus, when I read a memoir or other history about either of those countries, I have an insight and a deeply felt engagement other readers, who have not lived there, can never have. Therefore it follows, for me anyway, that I can only attempt to do any justice to books like To Quote Myself by also explicating and critiquing my own response to the book. In this light, the following three paragraphs are not so much about Khaya’s book, but how books like his move me in turn to write about the South Africa I feel “should” be written about – so as to understand better the (sometimes unexamined) assumptions and values I have as I consider his memoir.

When I think of South Africa, the process is not conventional thought. It is too much of a private experience to merely call it “wordable” thinking. So, when I put down for a moment books about South Africa, including Jani Confidential or Summertime, something is breathed in and out of me that is not only air as I sit among the foreign trees, such as the pohutukowas, here on our deck in Brown’s Bay, New Zealand. After a few moments, eyes closed or open, the colours of the Cape, the Drakensberg and the Cedarberg stir in me, trembling and astonishing, like watching the pollen or rich soil blown in plumes from a child’s hand. Like nostalgia, some still clings to her uplifted palm. Thereafter … the wind-misted dust of a solitary plaas road. The dust is the colour of fragrant orange in the African sun, which is absorbed by the ice of evening light on African hills. In memory (in this moment, what else is there?) it all become blood, the blood of sacrifice and violence, darkening further on hillside stone, giving the hue of rust to stripped trees and – here – the massive ultra-violet of the shadow beneath Cape mountains. Here on my deck in Brown’s Bay, I sit mesmerised, then feel awkward about trying to write this personal experience which appears so exaggerated. But I let myself ache and sing with the sounds of my childhood and adult South Africa half a world away from Khaya’s. Oh, the mountain landscapes where I hiked, the townships where I walked or drove through, the alleyways of a forgotten Hillbrow, and the corridors of a half-remembered boarding school I attended for many years. The frighteningly still roads of Langa during a teacher’s strike around the “black” “township” school I once taught at … Ja, the colours and feels of it are all rain-fresh, rain-darkened and electrifying as eels slithering over my hands in the sea.

The momentousness of leaving the place of one’s birth and upbringing.

Like an umbilical cord the long dusty roads between Johannesburg and Cape Town, between Grahamstown and Durban … You see, all this jumble of descriptions cannot be only thinking about the ou land. It is all tactile against my skin as chunks of sharp quartz and gravel. It churns in my belly. The stones remind me of rocks I hurled as a child at cats in trees or other boys, often ones of Afrikaner descent. Or seeing angry black youths hurling them at cars in townships. My own car was nearly destroyed with rocks when I was teaching at a so-called “black” “township” school in 1989. Stones: cold as Atlantic rain, sharp and cruel as lightning, bruising skin of any colour. Ja, South Africa and her history of stones, of klippe.

So, if I were to write a “template”, that is to say, a set of expectations for what I want from a memoir about South Africa, the heartache and the guts of a country torn apart by an entrenched class system and racism, the above three paragraphs would almost cover it. My “thoughts” about South Africa are somewhat romanticised, overblown, with too much pathos (when I put it on paper). But that is the movement from the intense moment of meditation (where the word nostalgia does not really do) to mere words trying to capture the experience of “re-living” or rather, almost inventing the past. It would probably be unfair on any South African memoir writer to be judged by these expectations, now that I confront them on paper. But I do expect something to be written – that actually gets published – which goes into the guts and balls of a fascinating, bloody and colourful country. These were and are the standards I brought to Khaya Dlanga’s memoir. However, I will add that the expectations I brought to his book were also based on the wonderful short story he wrote here, which is the best piece I have read on Thought Leader. There, Khaya writes about his childhood perception of the myth (not the man) Nelson Mandela. Speaking as a whitey, I thought the tale captured something of the heart of what it means to be a “rural black”, specifically a Xhosa child growing up in a country still darkened by apartheid-on-paper, through which was beginning to course the so-called “winds of change”, heralded by Mandela and De Klerk.

Ah, Mandela. In those times that name was spoken by us all in hushed terms. He was a scary, unseen tatamkhulu. Though then still imprisoned, his presence was growing everywhere with a messianic feel. Madiba: a warrior and a healer archetype which resonates throughout Khaya’s poetic writing in that Thought Leader piece. Almost inevitably, going by the unkind, even prejudiced standards I realised I had when reading To Quote Myself and the bar Khaya set with that piece on Madiba (which finds its way in a disappointingly edited form in the memoir), there are some parts of his book which don’t reach that standard. (There are many that do.) These weaker areas are the anecdotes about ad-man Khaya’s corporate life.

His reflections on his advertising career are often bland. They are greyly corporate, and form a cloned, ho-hum success story. The name dropping of ad agency “celebrities” makes one start to skim; I wince at any suggestion of arse-licking, especially the hero-worship reflections on senior personnel in that great corporate temple, Coca-Cola. That institution is one of the capitalistic rivals to the Catholic Church, filled with sycophantic acolytes and its own deep culture of money-worship based on poisoning children. I winced as Khaya shared all their great ideas on “mentoring” and “communicative strategy”, when the bottom line is a McDonaldised insipidity that had nothing to do with the uniqueness of being born on the edge of significant changes in South Africa. Coca-Cola and KFC were mindlessly consumed before, during and after 1994 in South Africa. Mentioning in passing various “success” stories, for example a black businesswoman who refuses to style her African hair after a European woman’s, as if that were some kind of meaningful sacrifice, had me cringing. I found myself asking, why should the rise of yet another young man in the advertising world that could be anywhere on the globe ( especially after his vivid reminiscences about his Xhosa childhood in the tiny village of Dutyini in rural Transkei and being homeless and half-starving at times while he studied at AAA in Cape Town ) be of any interest, indeed, be publishable? Is it simply because Khaya is “black” and therefore more marketable? Should a whitey be suggesting how Khaya should write his own memoir?

(To be continued … )

Follow Rod on Twitter @Rod_in_China