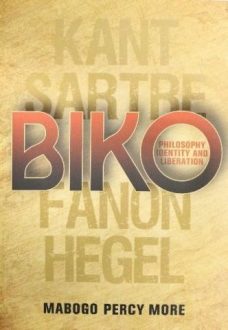

Reading Biko: Philosophy, Identity and Liberation by Professor Mabogo Percy More; I am left to wonder of the man (Bantu Stephen “Steve” Biko) who should have been king; that is the man who should have been the first black president of the Republic of South Africa. Or is that racist? Perhaps I should say, the first democratically-elected president of the Republic of South Africa? Biko was post-Mandela. Mandela was already in prison when Biko caught the attention of the people. Sadly Biko was murdered by the police long before the unbanning of the ANC, and the release of the political prisoners.

Reading Biko: Philosophy, Identity and Liberation by Professor Mabogo Percy More; I am left to wonder of the man (Bantu Stephen “Steve” Biko) who should have been king; that is the man who should have been the first black president of the Republic of South Africa. Or is that racist? Perhaps I should say, the first democratically-elected president of the Republic of South Africa? Biko was post-Mandela. Mandela was already in prison when Biko caught the attention of the people. Sadly Biko was murdered by the police long before the unbanning of the ANC, and the release of the political prisoners.

Biko was one of the founders of the South African Student Organisation (Saso) which became, after the unbanning of the ANC in 1990, the South African Students’ Congress (Sasco), in 1991. For many years Sasco was the most presumptuous student voice, casting flagrant demands at the African National Congress and the ANC Youth League, while dangling the support of Sasco and Cosas for the ANC as bait. All too often the ANC was baited and caught without so much as a whimper.

Professor More contends that Biko was a philosopher, who did not set out to become a philosopher. Rather that Biko attempted to arrive at solutions to the problems he faced and did so, without special fanfare, in, firstly, an academic manner, and, secondly, in a resultantly philosophical manner. More associates Biko with Fanon, Nkrumah and Nyerere; who similarly did not set out to become philosophers. All of them sought to critique and demystify the colonialism experienced by Africa and African people; and eventually became proponents of African philosophy as a result of which.

More cites Biko as a rebel who personally sought to undo injustice, and thereby became something more than just a rebellious youth. Biko’s authenticity (unlike what Fanon describes as the disposition of the colonised national bourgeoisie) as an African, who approaches the solution of an African problem from an African perspective, results in Biko exhibiting philosophical tendencies, that set Biko up to become an influential voice in the struggle against racism, colonialism and apartheid.

Black consciousness is discussed in quite a detailed manner, that leaves the reader feeling that an injustice has been done to the proponents of black consciousness. Contextualising black consciousness in terms of Black Power, Senghor and Fanon; More finds a way to soften black consciousness so that it is not simply considered to be “reverse racism” or worse “black-originated hatred”. More says:

Black Consciousness is a form of consciousness. This fact situates Black Consciousness within the ambit of phenomenology precisely because …, phenomenology is the study of phenomena as they appear to consciousness — that is, reality as constituted by consciousness in the sense in which consciousness is understood as always consciousness of something.

To further his argument in favour of Biko’s status as a philosopher, More spends an entire chapter summarising Philosophy 1, 2 and 3. Whilst doing so, he relates and correlates the context of Biko’s resultant philosophical tradition to the mainstream of philosophy. In other works More has justified Biko as philosopher while contending that philosophy and philosophers, borne of establishment and professionalism, would not recognise Biko as a philosopher.

Next More looks at the relationship between Biko and philosophy, almost preparing the reader for an assault that will force one to accept Biko as a philosopher. In “Consciousness as freedom”, More claims:

A black consciousness is a consciousness that is conscious of its blackness or of its body as black in an antiblack world.

While later distinguishing Biko as a “philosopher of action” whose very existence (and philosophy) was “…a threat and a danger to white hegemony…”

Having built up the definition of Biko’s resultant philosophical tradition as being that of Africana Existentialism, More ploughs on to attack racism and hypocrisy of racists, who while claiming the benefits of humanity for themselves, deny to their victims any humanity at all. He interrupts his discourse on racism to contend that apartheid was a system designed to keep the majority of the population (of black people) in a state of slavery or neo-slavery, for the benefit of the minority of the population (of white people).

I will not, on principle, mention the next two chapters which deal with Liberalism and Biko’s relationship with Liberalism and Liberals. Suffice to say, that I recommend it as reading for any Liberal wanting to know what is wrong with Liberalism, such that Liberals and Liberal Parties dare not mention it by name. Further to which I remember fondly Professor More chiding my Liberalism and contending that it was irreconcilable with my “pan-Africanist” Open Society beliefs; and as a result of which I will only say that More is correct when he states that the core of Liberal social ontology is individualism. I also remember Professor More disagreeing with my assertion that Biko was a Liberal simply because he propounded his own opinion and did not advocate a position that was the lowest common denominator, or worse made up of the lowest common denominators, of the opinions of the peoples that he represented.

Finally, after must prevarication, More arrives at the meat and potatoes. Biko and Marx. Here the Marxists are recorded as accusing Biko (and company) of “promoting middle-class values and a bourgeois philosophy”. Strange that Biko, the champion of Azania, should fall foul of the state-subsidised logic of Marx and the socialists. We have been fed a fact-lean diet by the Mbekis that says, that the cause of African Nationalism and the cause of African Socialism are in fact one. We have already seen that Biko, through Saso and Azaso and SANSCO and Nusas, co-founded Sasco which champions ANC policy; so why is it that the roots of the SACP and Cosatu and Sanco (being the ANC’s bridesmaids) decried Biko’s works as “middle-class”?

To contextualise More’s excursion, I must note that Biko called the Liberals “oppressive” and the Liberals called Biko “racist”; while Biko dealt with the Marxists on the basis that the Marxists were “disingenuous” and the Marxists called Biko a “liberal”. More says that Biko criticised the Marxists as not be authentic Marxists, merely privileged white people who had adopted a class-struggle-analysis.

At last the thing that made Biko famous, Liberation, is addressed. Sounding like Fanon, Biko contends that “…Liberal integration is a trick to foist white norms and values upon black people and thus achieve black assimilation into white culture, norms and values…”. More attempts here to deal with alienation, and to locate black consciousness in a space that “Marxistises” Biko by suggesting that Biko was dealing with the problem of alienation in his Africana Existentialism which became known in part as “black consciousness”.

More concludes with the assertion that “Black consciousness can thus be seen both as a philosophy of problematic ontology and a philosophy of existential (political, social, religious and cultural) freedom from that very problematic ontology”. I cannot stress enough the need for everyone who has anything to do with politics in South Africa, to read this book and to imbibe the logic of Biko, through More’s perspective’s argument. It will be a very long time before I am prepared to accept the very possibility that the natural course of Africanism, African nationalism, Pan Africanism and/or Azanianism is a socialist, Marxist or conservative one.