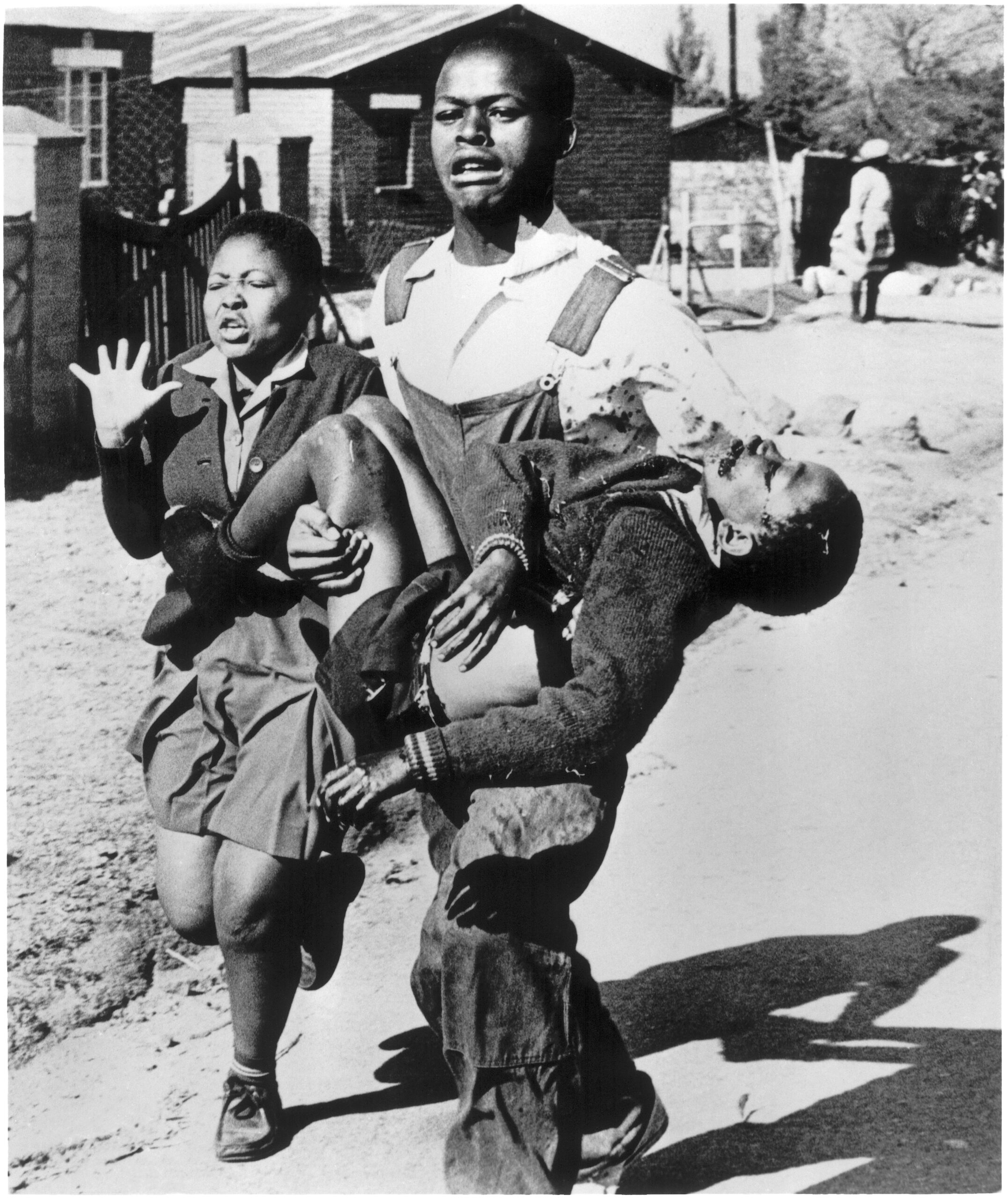

Stare too long at either of the three faces and a distinctly troubling sensation overwhelms you. You may look to Antoinette Sithole on the far left, and quickly turn your eyes away in a similar kind of pained disbelief. Look to the face of Mbuyisa Makhubu, 18 at the time, and you too may stifle your own raging cry of anguish. Look to Hector Pieterson in his arms, and perhaps your expression is a combination of the two others’ in the frame. Consider Sam Nzima behind the camera — which is to say consider the frame as a whole — and like me you may battle to find the words. In fact, I remember clearly that the first time I was shown this image as a young child, after a couple of seconds, I looked away.

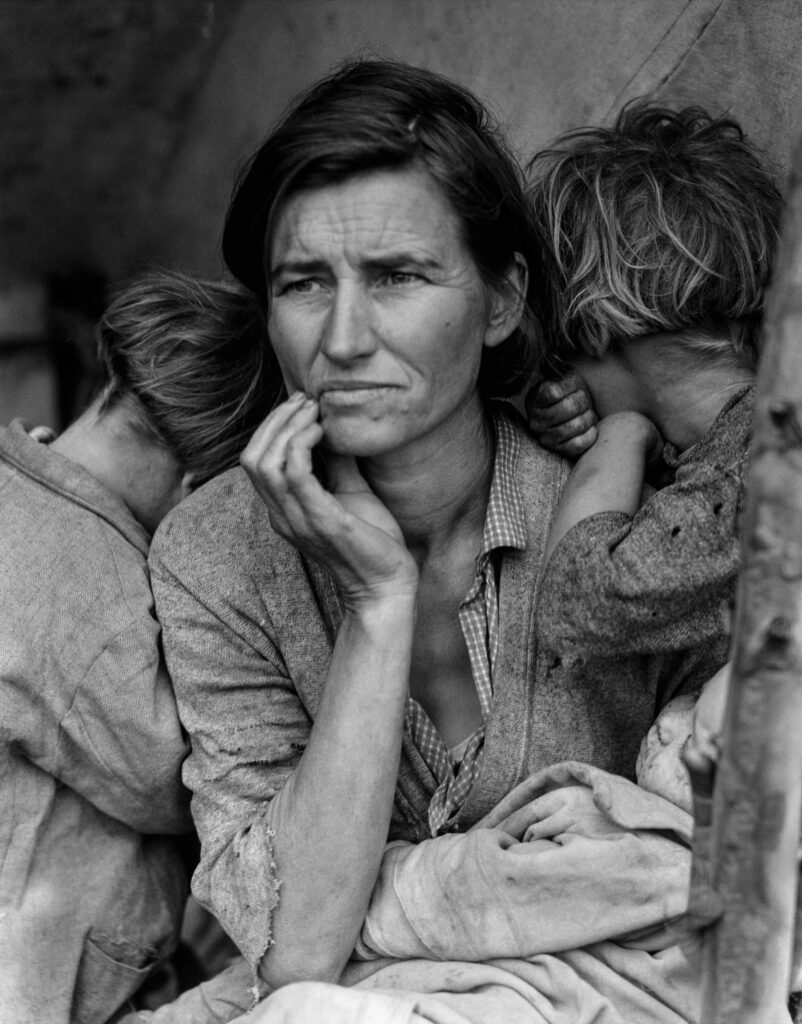

This iconic photograph appears in Time’s 100 Most Influential Images Of All Time as the “photo that galvanised the world against apartheid”. It and others like it — Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Malcolm Browne’s The Burning Monk, Eddie Adams’ photo of a Saigon execution– are some of the many images over time that have had a genuine hand in turning the tide of history. Although their striking compositions may give off the impression that these were merely “right place, right time,” moments, it is no coincidence that history’s watersheds each seem to come with their own watermark. In one way or another, landmark photographs similar to Nzima’s pull at our collective heartstrings, and our personal responses to them illustrate a broader historical phenomenon.

In her 2003 book-length essay Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag explored (among other ideas) the effectiveness of war photographs in convincing the general public of the atrocity and inhumanity of war. While much of her commentary is based on photographs taken during the First and Second World Wars, the questions she raises continue to resonate today.

At one point she writes, “Photographs are a means of making ‘real’ (or more ‘real’) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore. Look, the photographs say, this is what it’s like.” While I might rely on the accounts of my parents’ experiences of apartheid South Africa, and grapple with all there is to be found inside my history textbook, I know that I will never truly understand the adversity and sacrifices of the 1976 youth. I can, however, get a glimpse into them.

Both the immediate and the enduring effects of Nzima’s photograph are evidence that images have an unparalleled ability to communicate a story – a history – within seconds. In this way, an image sent out into the world has the power to shed light on concealed realities, to bring into the spotlight disregarded communities or individuals, and ultimately to foreground silenced voices.

Sam Nzima’s photograph of Hector Pieterson did that and more. In the 45 years since, the power of the image has only grown in effect.

Look to the many devastating images capturing the plight of Palestinians today and you see why neutrality is not the answer. With a higher frequency than ever, we have increasingly relied on visual media to elicit public response to injustice.

As a consequence, the question is no longer so much about effect and impact as it is about authenticity and ethics. As Sontag later goes on to contend, the realities and the emotions contained within one set of images “should not distract you from asking what pictures, whose cruelties, whose deaths are not being shown.”

Because what you might not know about this image is that Mbuyisa Makhubu, the man holding Hector Pieterson in his arms, disappeared shortly after it was taken. He fled into exile due to consistent police harassment and to this day nobody can account for his whereabouts. We know all too well that South Africa’s liberation would not have been achieved without immense personal sacrifice, but this example raises an important question. Which outweighs which: the effect that a photograph can have in building public consensus against injustice or suffering, or the protection of the private lives of the photo’s subjects? Any attempt to find a single answer feels futile. Authentic, purposeful media must find itself somewhere in the middle, stressing both considerations hand in hand.

What remains is that Sam Nzima’s photograph marked a turning point in the apartheid struggle — no longer were those removed from its context being told of the inhumanity of apartheid, they were being shown it. They saw faces. The same goes for the many other photographs over time that have visualised human suffering.

“Violence turns anybody subjected to it into a thing,” Sontag writes. What still photographs do is that they truly humanise the cost of injustice or oppression or marginalisation. They humanise these acts because, to an extent greater than any other medium, through their viscerality they evoke empathy and compassion. We begin to look beyond words on a page or statistics on a data sheet, and instead begin to see the faces at the centre of it all.

As we combat the plethora of injustices facing our societies through continued, intersectional activism, photography ought to continue acting as an entry point. In our digitised world, the disempowered are voiceless in too much of our contemporary discourse. Those most in need of our collective attention seldom get it. History shows us that perhaps the way through this is authentic, intentional and deeply personal photojournalism.

When I look back at the first time I saw Sam Nzima’s photograph, I see now that I shouldn’t have looked away. And so from here on out I’m not looking away; I’m paying closer attention to the images I see and the many layers to them. I am making the conscious decision to see the humanity in each individual in the frame, because I believe that when we do that – when we let our responses to the pain of others be guided by empathy and compassion – we allow ourselves to be moved towards activism, towards advocacy, and towards justice.

This piece was published through a partnership between the Mail & Guardian’s Thought Leader website and youth platform Ukuzibuza.com to acknowledge young voices during Youth Month.