How often do we hear and become frustrated about how “wrong” things are in our democracy? The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted just how unhealed and divided this country can be. Two decades into democracy, we still don’t truly see each other. And why? Because we haven’t gone through the process of healing this country’s collective consciousness from the long trauma we endured as a nation.

Yes, economic transformation must happen first. But what frames how we carry this out and how those in the private and public sector help to make the changes we need is determined by how we regard each other.

Science tells us that trauma lives in our DNA – from slavery to apartheid. We carry it with us, whether we acknowledge it or not. When we ask: “What went wrong?”; “How did we get here?” or “How could such a long road turn onto this path?”, perhaps one of the answers is that too few of us have the will to dig deeper, to penetrate the layers of democracy enough to shift our perspectives.

Considering South Africa’s history and witnessing the psychological mess we are in today, why do South Africans not honour and respect those who suffered for justice and freedom? It is after, all, set out for us in our Constitution.

Storytelling is one of the answers

A proven way of healing exists — storytelling. From the Nuremberg Trials to the Northern Ireland conflict, from Guatemala to Somalia, results have shown that when we learn about others and our past, engage with it and receive it, we heal.

If we have to consider bookends to the struggle for freedom in South Africa, starting with passive resistance and ending with armed resistance, there are reams of stories in between. Along the way were the women’s march of 1956, the 1960 state of emergency, the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the Soweto uprising in 1976 … years and years until freedom arrived. What filled the minutiae of the minutes and days that went on and on for those years?

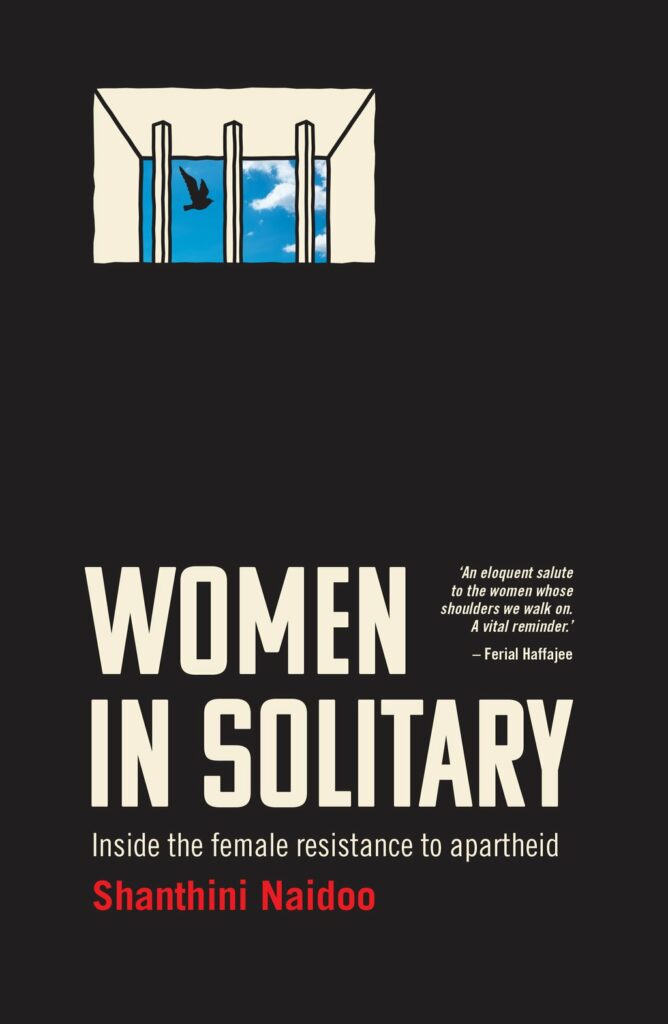

The women in my book Women in Solitary: Inside the Female Resistance to Apartheid were part of a treason trial, the Trial of the 22 of 1969, which isn’t widely recognised. Yet Nomzamo Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Martha Dhlamini, Thokozile Mngoma, Rita Ndzanga, Nondwe Mankahla, Joyce Sikhakhane and Shanthie Naidoo changed the course of our history. Kept in solitary confinement and tortured to testify against each other, their refusal to turn on each other saw the trial collapse. They were released after a year spent in dark, damp, lonely cells. Their work continued after, as the leadership were in prison. We did not know this story and its effects.

The courage and sacrifices they made are important in giving greater visibility to both the tangible and intangible contributions women made in the liberation struggle in South Africa. If, as the science suggests, we carry them in our DNA, a deeper exploration will allow a deeper understanding.

Few of the older “struggle generation” have sought psychological help for the emotional trauma they suffered as a result of standing up for their political beliefs. It is my view that the outcomes continue to be reflected in South African society today.

Judy Seidman, a board member of the Khulumani Support Group for those affected by apartheid, wrote that “at the end of so much digging for the truth in the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission], so many people found themselves still bleeding from open wounds. [Women had] entrenched personal memories of the ongoing violations in the name of apartheid and connected these gendered apartheid violations with the grim consequences affecting women survivors in the post-apartheid era. They explain that black women in South Africa as a group remain mired down in poverty, without resources, without economic security, with no way out.”

One of the most significant shortcomings was that the TRC did not document gender-based violence against women.

“It was simply subsumed under the broader heading of ‘serious ill-treatment’,” Seidman wrote. “When women were interviewed by TRC statement-takers against their list of prepared questions used by the statement-takers, no questions about rape and gender-based violence were asked and if a woman spoke about being raped or experiencing gender-based violence, the statement-taker usually did not record it.”

And, as Professor Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela’s research on the TRC reveals, healing and empathy, before forgiveness, all come from storytelling. She says: “South African society has several decades of formalised dysfunction from which to recover, and several hundred years of colonialism before then.”

The economic gap remains, because supporting people’s healing without attending to their desperate needs for economic survival “merely unlocked more trauma so that most survivors of atrocities still live today in states of continuing extreme stress”.

Gobodo-Madikizela’s research after her years of work documenting the TRC now focuses on two areas of “moving forward”. One is how “dehumanising experiences of oppression and violent abuse continue to play out in the next generation in the aftermath of historical trauma”. The second research area expands her work on forgiveness and remorse, and probes the role of empathy more deeply, including trans-generational trauma.

“The descendants now face the double jeopardy of the transgenerational repercussions of apartheid’s corruption, and the failures of some politicians in our contemporary government in their moral duty to act in ways that would reduce the suffering of the descendants of those who were oppressed under apartheid.”

Remorse over forgiveness

This, Gobodo-Madikizela says, is because the narrative about South Africa’s history incorrectly centred on forgiveness — implying forgetting and moving on when we were not ready.

Remorse, on the other hand, is a reclaiming of the conscience.

The first psychological step towards this is in acknowledgement. “This is so crucial to survivors of traumatic experiences. Public processes of accountability, such as when perpetrators confess to massive human rights crimes, are an important form of recognition that helps survivors feel a sense of affirmation and validation,” she says. “One of the tragic consequences of trauma is a loss of victims’ sense of agency.”

The trauma from apartheid, which we still hold in our bodies and carry into our relationships, bleeds into different forms of violence. Some trauma is internalised as depression, loss of dignity or self-worth.

These everyday traumas can similarly be found in the microaggressions that plague middle-class South Africans today. K-word trauma, road rage that turns racial and boardroom politics are some examples. Major aggressions, such as the link to trauma for those who are now the perpetrators of GBV, must not be forgotten.

To begin, we must know the stories and share them, digest and understand them. This is why stories from our rich history can open our minds and consciousness on the path to healing.