https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHFPi_3kc1U

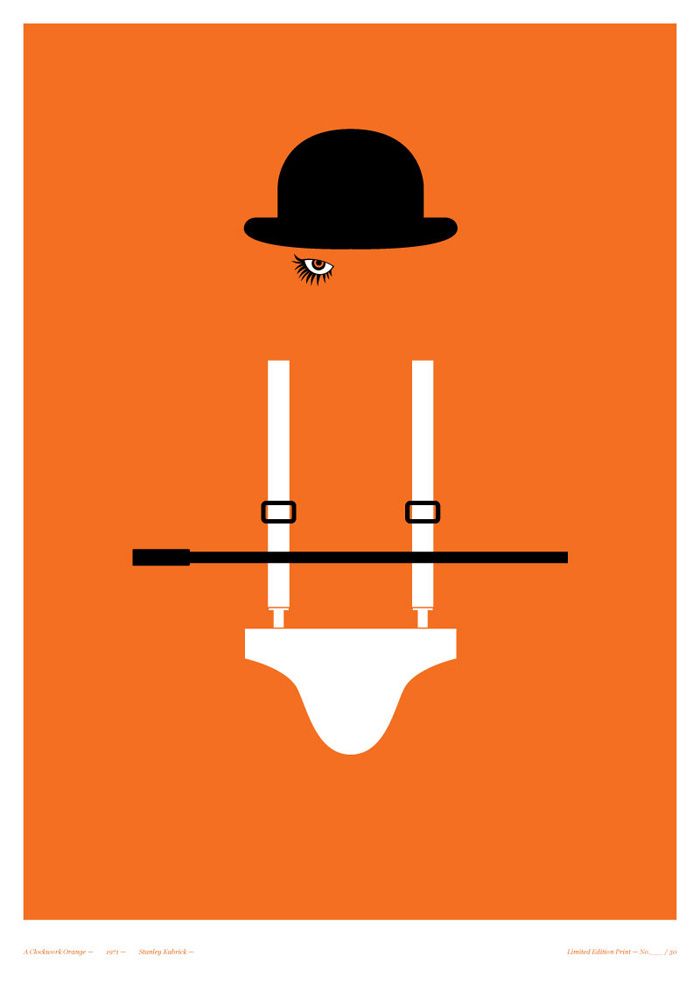

There is a haunting and chilling scene in the film A Clockwork Orange that makes even the most resolute among us shudder. It’s also a moment that quite gorgeously sees the perfect unification of Stanley Kubrick’s deft control of the visual with Anthony Burgess’s honey-dripping command of words.

The camera settles on the bottle of an old drunk lying under a bridge, somewhat tunefully singing Molly Malone. “In Dublin’s fair city, Where the girls are so pretty, I first set my eyes on sweet Molly Malone.” The camera slowly pans out and before the drunk can sing “alive, alive oh” the foreboding shadows of Alex DeLarge and his droogs shoot from the light at the end of the tunnel and cast themselves over the hapless man.

The camera further pans out so we can see the shadows’ menacing creators, complete with Bova boots, bats and belligerence. “One thing I could never stand was to see,” says Alex with a mellifluous yet sinister voice that you will never forget, “a filthy dirty old drunky howling away at the filthy songs of his fathers and going blurp blurp in between as it might be a filthy old orchestra in his stinking rotten guts; I could never stand to see anyone like that, whatever his age might be, but more especially when he was real old like this one was.” The droogs then let their boots, bats and belligerence fall upon the man with sickening glee. And so a beautiful scene of cinematic excellence is created.

We are the drunky and Alex DeLarge is Covid-19.

Well, that is certainly how it feels after the president’s speech announcing the move to stage four of the coronavirus lockdown, we prepare to amble cautiously into the alleyways of virus-infected South Africa. We know the dangers and expect that at some point, we will have the Molly Malone beaten out of us. And ,like most dystopian movies, we are in that stage of acknowledging the threat; we have a pretty good idea what’s about to come, but we have no idea how to live in this reality. Lying drunk in the alleyway is not an option. It’s that eerie calm when we hear the leaves rustling in the wind and have only just realised that the trees are talking to one another. Lockdown security and physical distancing is protecting us, but it is a protection that is about to be lifted and we are not entirely sure of the consequences.

South Africa’s apocalypse is about to begin, while so many countries in the world are either well into it or are already putting their broken psyches back together again. Their nuclear winter is being replaced with the sounds, sights and joys of spring, while we slowly enter the season of hibernation and death. Gracious, that all sounds so woefully hyperbolic. Of course, this is not really an apocalypse and I have previously bemoaned the use of the word by the press, but I have chosen this analogy and I am going to stick with it. Besides, it is the dystopian feeling and sense of impending personal apocalypse to which I am referring.

This feeling exists because, if nothing else, the lockdown has made us feel both safe and unsure about what’s out there prowling the streets. We are in an eerie limbo. We want to go out and sing in the rain, but we know that we will have to do it, not only with an umbrella, but in full personal protective equipment. We know that our infection rate is low compared to many other countries, but have an extremely good guess that our desire to live will increase our chances of dying. We know the reality that the virus creates and are lost in the reality that we desire. It is a complicated state in which to live and, with the easing of the lockdown, psychologists are in the rand seats.

Of course, this is probably an over analysis of a simple problem, which is how we respond to threats. Anyone who suffers from anxiety will tell you that we are hard-wired to see threats as fatal. All those millennia ago when we were naked (or wearing fetching little loincloth numbers) and running through the bush in search of food, the only fear we truly had was the fear of death or injury (which would invariably lead to death) and so our bodies reacted dramatically and prepared us to respond to the threat.

Because the threat was always physical, so was our response: our heart rates increased to speed circulation; our rate and depth of breathing increased to speed gas exchange; we sweated excessively to promote slipperiness; glucose synthesis increased to provide energy; blood was redirected from the gut and skin to muscles; muscle tension was increased to improve strength and endurance; and even blood clotting was increased in preparation for possible tissue damage.

These are really clever responses (thanks, God) that played an important role in the survival of mankind. However, sadly, evolution moves at a slower pace than human progression and now, in the vastly different lives to those of our early forefathers, threats are not fatal, seldom physical and we are often debilitated by our bodies responding in such a way to save us from being mauled to death by a pride of lions, when in reality we just can’t choose whether to have rice or noodles with our Massaman curry.

Admittedly, the threat of our lungs collapsing due to a virus is more serious than our selection of (takeaway at level two) starches. But when I am confronted with these anxieties, I do what so many atheists do: I turn to God. “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.” Of course, I am not really asking God to grant me anything, but I (and from what I understand, every 12-stepper out there) find these words both comforting and helpful.

Although serenity isn’t always easy to come by, especially when what you can’t control is Alex DeLarge and his milk-plus intoxicated droogs. Still I will see the opening of our lives in a government controlled and difficult to really understand five-levelled approach with a sense of cautious wonder. I will wander the streets with the knowledge that our books are not going to be burned; that the robots haven’t taken over; that we don’t live in a World State whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy, or that there is omnipresent government surveillance. No, I will walk out singing in the rain to a brave new world, because although we are the drunky, Alex is not Covid-19, but rather, our own fears.